|

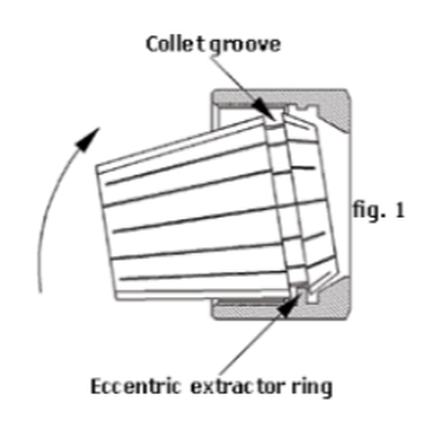

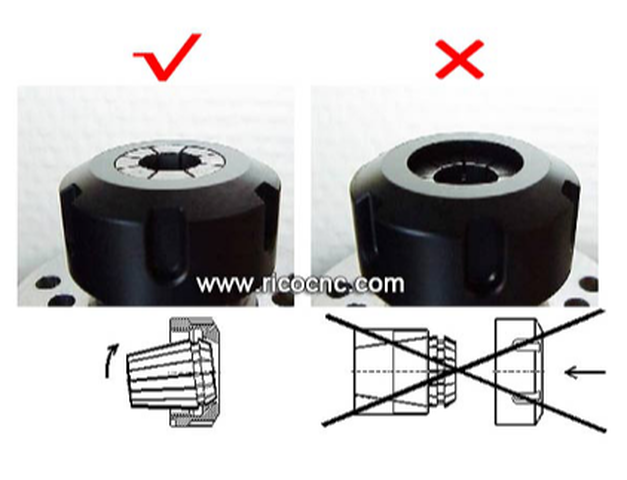

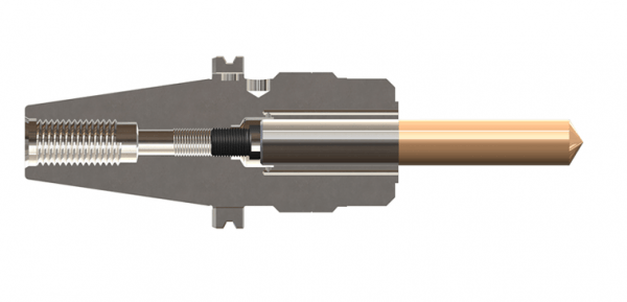

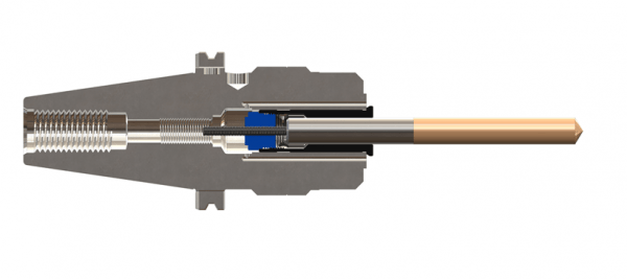

It is critical to properly assemble the collet and collet nut to avoid damage to the collet and make the most accurate and rigid assembly possible. The extraction groove of the collet must be properly seated to the extraction ring of the collet nut. If the collet extraction groove is not properly seated to the collet nut extraction ring, the collet will appear seated below the face of the nut. This typically occurs when the collet is placed in the collet pocket of the tool holder and then the nut is threaded on the tool holder. In a correct assembly, the collet will seat at the face of the collet nut. The image below shows a correct assembly on the left and an incorrect assembly on the right. DO NOT tighten the collet nut if the collet appears seated below the face of the nut as this will create galling on the 30° face of the collet. Galling appear as grooves or lines in the lead face of the collet. Recognize Galling on Your ER ColletGalling on the lead face of the collet can result in reduced clamping pressure on the cutting tool shank that may lead to the cutting tool slipping while cutting, or even tool breakage.

0 Comments

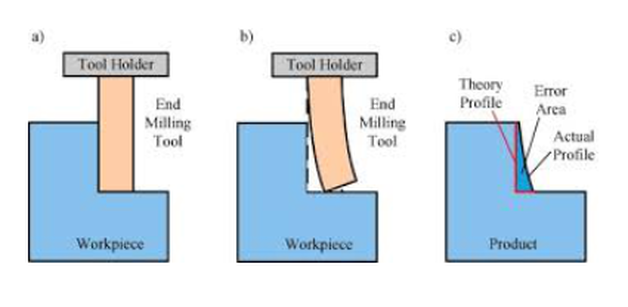

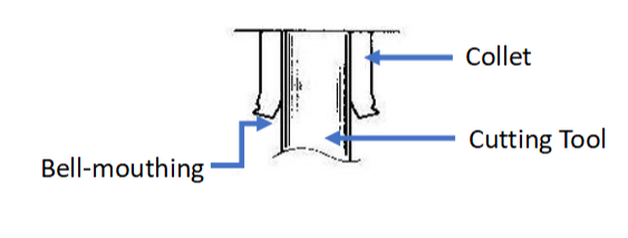

Technical Blog excerpt courtesy of Techniks USA It is important to understand how collets work, what impacts their performance, how to maintain collets for long service life, and how to recognize when to replace them. Collets are a high-precision wear component of a tool holding system and require maintenance to ensure accuracy. First, it’s important to remember that collets are the softest component in a collet-based tool-holding system assembly and are designed to wear out. Here is an overview of the wear pattern of a collet-based tool-holding system. The machine spindle is harder than the tool holder/collet chuck that fits into the spindle, so any wear between these two components will mostly occur to the collet chuck. That’s good. It protects the spindle from expensive maintenance. Collets are softer than both the collet chuck body and the cutting tool, so any wear forces between these items will mostly occur to the collet. Since collets are generally the least expensive component in a collet chuck tool holding system, it is preferred that the collets wear out before the other components. Worn-out collets will not achieve the same level of accuracy and rigidity that newer collets can provide. The result is more chatter when cutting workpieces, less accuracy, and shorter cutting tool life. When to Replace ColletsCollets are designed to wear out as they lose accuracy and rigidity with use. High side-load forces during milling operations cause cutting tool deflection as illustrated below. Over time, these side-load forces will bell-mouth the collet at its face. As the collet experiences bell-mouthing, the cutting tool is allowed to deflect more and more during milling operations. Unfortunately, the collet may still indicate good accuracy on a presetter where there are no side-load forces. However, once the tool is put into service and begins experiencing side-load forces, the cutting tool is allowed more room to deflect, resulting in increased chatter and reduced tool life. It is recommended to change collets out every 4-6 months, depending on usage, to ensure the most rigid and accurate collet chuck assembly. A good rule of thumb is to replace collets every 4-6 months to maximize the performance of your tooling. Again, collets are designed to wear out and are generally the least expensive component in the system. It is much less expensive to replace the collets as opposed to prematurely wearing out cutting tools. The following tips will help you in maintaining collets:

Signs that Your Collet Should be Replaced

If you see signs of fretting on the collet, it is advised to replace the collet. You should also ensure that collet nuts are tightened to the correct torque specifications during setup.

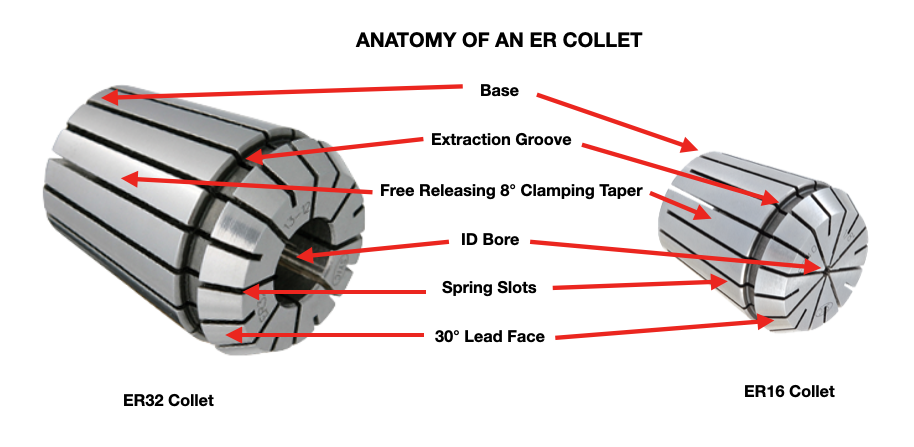

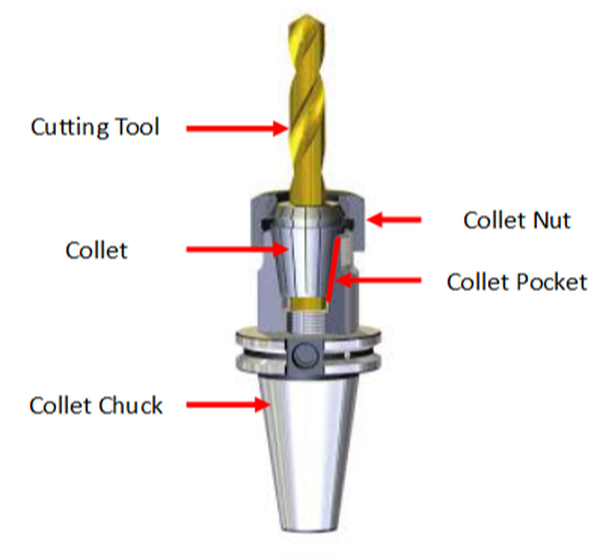

CLICK HERE to see all of our more in-depth articles on FRETTING to learn more. Edited by Bernard Martin If you work in the metalcutting, signmaking or cabinet making manufacturing industry, the term “collets” is already very familiar to you. There are many types of collets used in many different industries and applications. This article is focused on collets used in rotary tool holders found in CNC milling machining centers and CNC Routers and also used in CNC Lathes and Swiss Style CNC's. Let's cover the basics: What are Collets?Collets are the critical connection between the cutting tool and the tool holder, also called a collet chuck. Most collets are round, cone-shaped, and slotted. Collets encircle the cutting tool shank to evenly distribute holding power around its center bore. Before getting too deep into the technical aspect of collets, It's going to be helpful to anyone new to the use of collets to understand the basic anatomy of collets and of a collet chuck system. How Collets WorkThe tapered collet base is made to fit into the collet pocket of the collet chuck body. The free release locking tapered (16°included, 8° per side) design of the collet base and collet pocket allows the collet to be centered in the pocket as it is pushed in by the collet nut on the lead face during setup.

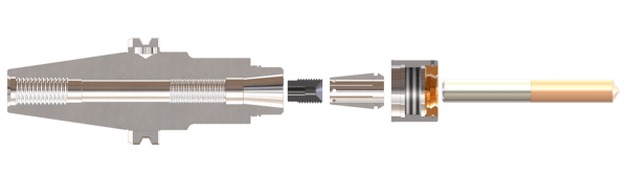

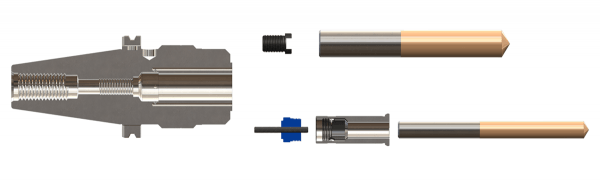

This centering effect enables the collet to achieve a high degree of accuracy (concentricity); much more than drill chucks and side-lock style end mill holders. As he collet nut is tightened down on the collet, it is pushed into the pocket collet chuck pocket. The slots in the collet allow the I.D. bore to collapse and apply clamping pressure to the cutting tool shank. It's essentially a spring that is compressed tight around the shank of the cutting tool such as a drill or end mill. The result is a very strong and rigid clamping force on the cutting tool. Since the collet base is tapered to match the collet pocket, tool runout (T.I.R.) is reduced. Total indicator runout (TIR) is a term often used in manufacturing, especially when dealing with rotating parts such as cutting tools, particularly endmills and drills. TIR is defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum values measured across an entire rotating surface about a reference axis. As the title implies adjusting screws, also known as back-up screws, stop screws and preset screws, are not just a simple set screw. They are a screw with a purpose--three actually. The first is to provide a fixed stop for a cutting tool to rest against during tool changes. This allows an operator to save time as they do not have to pull out a ruler, setting jig, etc. to reassemble the cutter into a holder. A secondary purpose of the adjusting screw is to assist the tool holder in keeping the cutter from being pushed up into the holder if the cutting loads increase to the point where the tool may slip up into the holder. The third is to offer sealing for coolant-through tools. 1. Expected repeatability of cutting tool lengthWhen an old cutter is swapped out and a new one put in its place, the repeatability of this process will vary based on a few parameters such as cleanliness and the OEM cutting tool overall length tolerances. Cleaning the clamping bore or collet of a holder provides better runout repeatability which should be old news to everyone, but if old coolant and contaminants are not removed, they would get jammed between the end face of the shank and the adjusting screw, affecting the length setting. Cutting tool overall length tolerances may also vary from one OEM to another. We have seen them range from ±.3mm to ±.5mm (±.012” to ±.019”). Others may be tighter or looser. Most modern machining centers come with tool length offset measurement systems which will provide the final precise gage length of a tool assembly. With the rough position provided by the adjusting screw, the machine operator can continue working and does not need to worry about tool clearances and stick outs. 2. Forms of adjusting screwsThe clamping mechanism of the holder also affects the length repeatability. Both hydraulic chucks and milling chucks are radial clamping systems, whereas a tapered collet is drawn down into a taper by a threaded nut. This draw down causes the cutter to be drawn down as well. For this we have two types of adjusting screws: HMA/HDA solid type and NBA rubberized type. The solid type is a one-piece steel construction part, whereas the rubberized type has a rubber padded conical pocket that absorbs the axial travel of the cutter shank as the collet is clamped. 3. Option for adjustable reduction sleeves for MEGA DS/HMCMilling chucks also have a second type of adjustment screw option that can be built into the back end of a reduction sleeve. As cutting tool diameters get smaller, the length of the shank also gets shorter. As such, the end face of the shank may not reach the HMA adjusting screw when installed it the body of the holder. The AC Type Collet adjuster screws into the back end of the reduction sleeve where the shank the tool can easily be reached. 4. Warning on holders that cannot support adjusting screwsIt is always recommended to consult the tool holder catalog or technical documentation to ensure that a holder can support an adjusting screw. Some holders are very short or have very deep internal features that may not allow for the use of any adjusting screw. In those cases, a depth setting ring or collar on the shank of the cutting tool may be an acceptable alternative.

Caution should be used on shrink-fit holders. Thermal expansion/contraction occurs in all three axes, so as the body of a shrink-fit holder cools down it will draw the cutter down jamming onto the adjusting screw. This could lead to damage to the screw, the holder or the cutter. It’s been estimated that a tool with a run-out of 50% of the tool’s chip load will reduce its tool-life by 40%. That means that a 1/8” tool with a 0.00019” chip load per tooth will lose 40% of its tool-life with a run-out of less than 0.0001”. Excessive and inconsistent run-out from a properly setup ER collet chuck assembly typically occurs due to friction build-up between the 30° face of the collet and the collet nut.

The result?

Other Parlec P3 collet advantages:

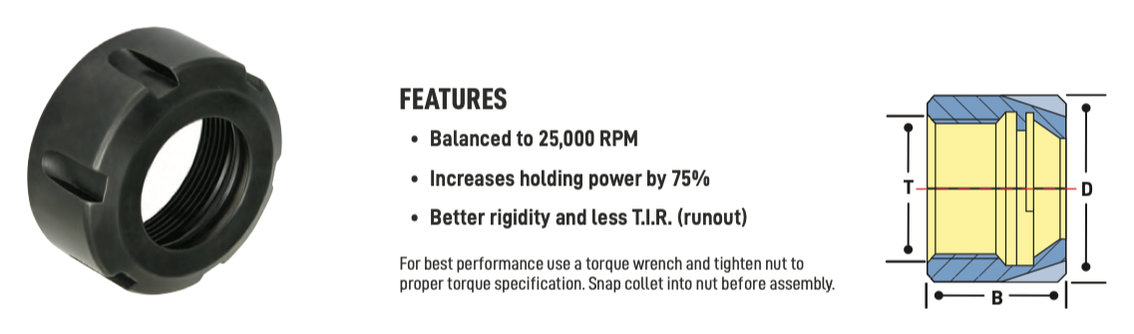

Don’t throw away you ER collet chucks to improve accuracy Try Parlec P3 collets and supercharge your ER collet system. Written and edited by Bernard Martin PowerCOAT Collet Nuts provide up to a 75% increase in holding power! One of the most important elements of the toolholding 'system' is the collet nut. Each toolholder "system" consists of a precision ER tool holder that comes with a special "Power Coated" high power nut that holds tighter than any other nuts. According to Techniks, the 'Power Coat' nut is the secret to their high holding power. Because it holds so tight, the 'Power Coat' nut improves T.I.R., extends carbide tool life, and improves finish in heavy milling operations. Techniks recommends that for best results always tighten the nut to the proper torque using a torque wrench with a tightening stand, and never over-tighten the nut because this can damage both the collet and the collet pocket. To demonstrate the difference between an uncoated and coated collet nut, Mike Eneix, from Techniks did some testing. He took an uncoated, imported nut and put it to the test against the Parlec PowerCOAT nut. Mike took them to the limit to see which one gives you more holding power. Check out the video below! What makes the difference?As anyone knows who has changed a flat tire on their car, tightening down a nut on a 60 degree thread involves some friction as the mating metal surfaces interact. That's why nuts can be a bit 'hot' to the touch when you take them off. The objective with the "Power Coated" nuts was multifold:

First Techniks needed to reduce the coefficient of friction on the thread angle to enable more lubricity for the nut to tighten down farther. As we all know 'heat' causes metal to "grow" so what may at first appear to be tight, in fact, loosens, as soon as you stop tightening it. Second they needed to make sure that the front surface of the collet that engages the shorter 30 degree taper on the front of an ER collet did not 'twist' as the night tightened down. Both problems really involved reducing friction and through a combination of engineering tolerances and unique coating process we believe that we've found the most economical solution to eliminate the use of cheater bars and collet over torque. Here's what they've found out in testing the "Power Coated" Nuts:

“Power Coat” is an innovative, permanent coating that increases clamping pressure of the nut up to 75% compared to standard ER nuts. More holding power reduces the chance of spinning the shank of the tool inside the collet, which can cause premature failure of the collet. The four critical requirements for tool holders are clamping force, concentricity, rigidity, and balance for high-spindle speeds. When these factors are dialed in just right, there’s nearly no chance of holder error and considerable cost reduction is achieved thanks to longer tool life and reduction of down-time due to tool changes. Easier said than done, our experts shared some of their best, quick-hitting advice for top tool holder performance in different situations. 1. Balance holders as a complete assembly Long-reach milling has some unique demands; when setting up this type of job, always balance tool holders as a complete assembly. While many tooling providers pre-balance their holders at the factory, it’s often inadequate, especially for long-reach applications. 2. Holder damage can go from bad to worse quickly Wear and tear on holders can be costly in the end, but there are ways to protect against it. Inspect and care for your holders. Trauma on a holder or spindle—dings, scratches, gouges, etc.—can magnify quickly. One bad holder can spread its problems like an illness. If you’re seeing disruptions like these on your holders, get them out of the rotation. 3. The rule of thumb on holder dimensions Looking for affordable ways to avoid vibration? Start by opting for a holder with a combination of the largest diameter and shortest length possible. 4. Rigidity can harm tapping operations What many don’t realize about tapping operations is that a perceived strength of collet chucks—their rigidity—can actually be detrimental. Rigidity does very little to counteract the dramatic thrust loads imposed on the tap and part, exacerbating the already difficult challenge of weathering the stop/reverse and maintaining synchronization. 5. Balancing is crucial to five-axis machining Five-axis machining introduces a whole new set of tooling challenges. While important in any type of machine, balance may be of most importance in full five-axis work. A well-balanced holder helps ensure the cutting edge of the end mill must be consistently engaged with the material in order to prevent chatter and poor surface finish quality. 6. Consider spindle speed requirements when choosing between shrink-fit and hydraulic holders If you have to choose between shrink-fit and hydraulic holders in a long-reach application, consider the spindle speed required. If a hydraulic chuck exceeds its rated RPM, fluid is pulled away from the holder’s internal gripping gland, causing loss of clamping force. But when used within its recommended operating range, a hydraulic tool holder offers superior runout and repeatability. On average, a good shrink-fit holder has about 0.0003-inch runout, while a hydraulic chuck offers 0.0001 inch or better. 7. Don’t overlook the tool’s effect on holder performance The cutting tool affects holding ability more than most machinists and engineers realize:

8. Not all dual-contact tooling is the same Anyone in the market for BIG-PLUS dual-contact tooling should consider this simple statement: Only a licensed supplier of BIG-PLUS has master gages that are traceable to the BIG grand master gages and have the dimensions and tolerances provided to make holders right. Everyone else is guessing and using a sample BIG-PLUS tool holder as their own master gage—a practice that any quality expert will advise against. Look for the marking: “BIG-PLUS Spindle System-License BIG DAISHOWA SEIKI.” 9. You may have a BIG-PLUS spindle and not even know it You’d be surprised how often we hear from our certified regrinders or engineers in the field about folks that didn’t realize their machine had a BIG-PLUS spindle—the message can get lost in the supply chain or during the sales process. The easiest way to know if an interface is BIG-PLUS is to place a standard tool into the spindle and see how much of a gap there is between the tool holder flange face and spindle face. Without BIG-PLUS, the standard gap should be visible, or about 0.12 in. If it is BIG-PLUS, the gap is half of this amount, or only 0.06 in. These values change depending on 30 taper, 40 taper or 50 taper sizes, but the gap is visibly less than usual. 10. Use positive offsets during holder setup It may be how it’s traditionally been done but touching off holder assemblies in each machine to establish negative tool offsets based on the zero-point surface—the vise, machine table, workpiece, etc.—is not the most efficient process. We think the choice is pretty clear: adapting machines to a single presetter so they can receive positive gage lengths is superior to using all types of machine-specific negative offsets.

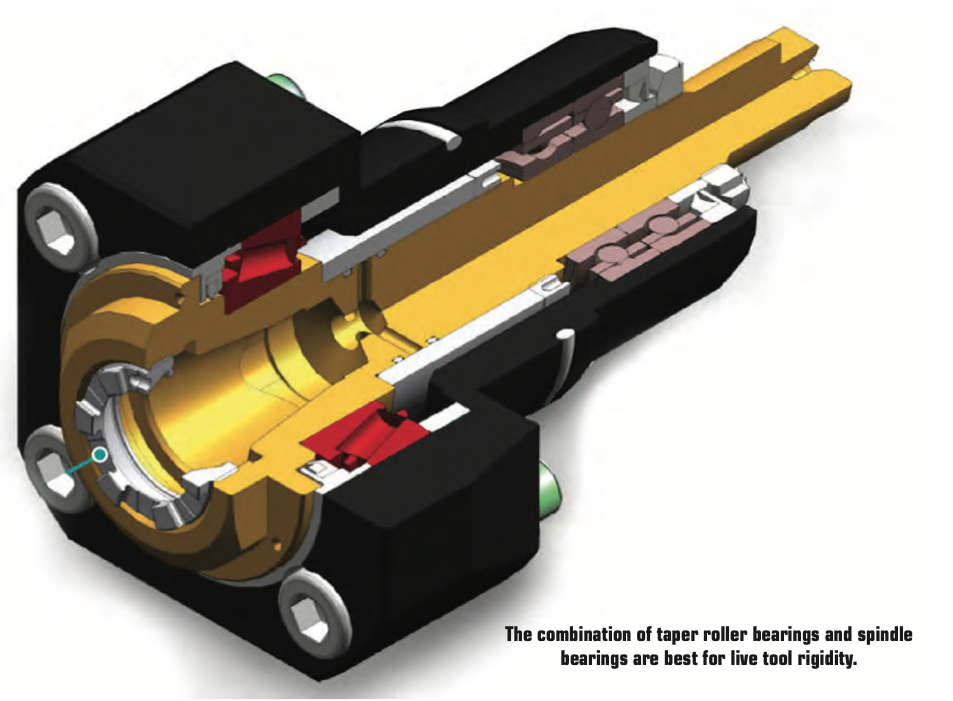

This is a change to “the way things have always been done” that can be met with some resistance, but in the grand scheme of things, it’s a relatively small and simple step that makes life much easier. It’s a relatively low-cost opportunity to introduce more standardization of holder setup to the shop floor. Holders are the bridge between the machine and the part. That’s a lot of pressure—literally and figuratively. It’s important to select, care for and use holders carefully from the day they are purchased until they’re tossed into the recycling bin. From collet chucks to coolant inducers, BIG KAISER is North America’s source for standard-bearing tool holders that guarantees high performance. Explore the full lineup. A REVIEW OF THIS MACHINING METHOD, THE BASIC CONCEPTS AND SOME EXCITING DEVELOPMENTS IN THE TECHNOLOGY by Preben Hansen, President, Platinum Tooling Technologies Inc. Live tooling, as a component on a lathe, is specifically manipulated by the CNC to perform various milling, drilling and other operations while the workpiece is being held in position by the main or sub spindle. These components, whether BMT or VDI, are also called driven tools, as opposed to static tools, that are used during turning operations. All live and static tools are built per the machine tool builder’s specification for each of the various models they produce. A key to running a successful job shop or production department is to partner with a supplier who can meet the tooling needs for all or most of the machines on your floor. Most often, live tooling is offered in standard straight and 90º angle head configurations with a wide range of tool output clamping systems, including ER collet chuck, arbor, Weldon, Capto, whistle notch, hydraulic, HSK, CAT, ABS and a variety of custom or proprietary systems developed by the many suppliers to the industry. When the need arises for a new machine tool, careful consideration should be made to determine which live tools are appropriate for your application. While a standard machine tool package will help you get started, it is important to anticipate job and volume changes, as well any unforeseen machining challenges from the beginning, in order to avoid machine downtime. This short article is meant to give you a set of parameters to consider when evaluating the live and static tooling to use in your shop or production department. Simply stated, you need to do as much evaluation of your process, when determining the proper tooling to be used, as you did when you evaluated the various machines available for purchase. This fact is often overlooked and that can be a critical error, in the long run. Your examination can range from the simple (external vs. internal coolant, for example) to the sublime (adjustable or multi-spindle configurations) to the custom tool, that may be required and built to suit your special application. Finding a supplier who has an in-house machine shop for the preparation of special tools is a great value-add. Tool life is the product of cutting intensity, materials processed, machine stability and, of course, piece parts produced. Two seemingly identical job shops can have vastly different tooling needs because one is automotive and one is medical, or one specializes in the one-off and low-volume work, while the other has a greater occurrence of longer running jobs. The totality of your operation determines the best tooling for the machines being purchased. Bearing construction and the resulting spindle concentricity drive the life of any tool. You might find that just a 10-15% greater investment in a better design can yield both longer lasting cutters and consistently superior finish on your products. Of course, the stability and rigidity of the machine tool are always critical factors. Bevel and spur gears that are hardened, ground and lapped in sets are best for smooth transition and maximum torque output. Taper roller bearings are consistently superior to spindle bearings in live tool milling applications, so look for a combination system to get the highest rigidity possible. Also, look for an internal vs. external collet nut, so the cutting tool seats more deeply in the tool, as superior performance will result. Likewise, high pressure internal coolant might be desirable. Look for 2000 psi capabilities in 90º tools and 1000 psi in straight tools.You need to ask another question, namely, is the turret RPM sufficient to handle the work to be done? It’s possible that a live tool with a built-in speed increaser, often called a speed multiplier, would be helpful. Would it be beneficial to move secondary operations to your lathe? Gear hobbing can be accomplished in this manner, as can producing squares or flats, through the use of polygon machining. Standard live tooling most often is best suited to production work, where the finish, tolerances and cutter life are critical, while quick-change systems may be better suited to the shop producing families of products and other applications where the tool presetting offline is a key factor in keeping the shop at maximum productivity. It’s a given in our industry that when the machine isn’t running, the money isn’t coming.

Dedicated tools for large families of products may often be desirable for some applications, but do consider whether a flexible changing system would be more appropriate. Talk to your tooling supplier for the various options, before making that determination. If standard ER tooling is suitable for the work, there are many good suppliers. It is important though, to pay close attention to the construction aspects noted above. For a quick-change or changeable adapter system, there are fewer suppliers in the market, so seek them out and be sure they can supply the product styles you need for all your lathe brands. Now, an application example showing clear evidence of the value of testing live tool performance... One company was performing a cross-milling application using an ER 32 output tool on a Eurotech lathe, running 10 ipm at 4000 rpm. They were making three passes with a cycle time of 262 seconds and were having difficulties with chatter on the finish, while producing 20,000 pieces per year. The annual cost of the machining was over $130,000. By using an alternative live tool with an ER 32AX output, internal collet nut design, with the same parameters, they were able to produce the part in a single pass with a smooth finish and cycle time of just 172 seconds. Over the course of the year, this yielded a cost savings of $45,000, approximately 20x the cost of the tool. The bottom line is the bottom line, as the accountants tell us. In the end, you may not need a universal adjustable tool or a multi-spindle live holder or even a quick-change adapter system but do consider all these options. Talk to your machine builder and several tool suppliers, plus the most important people in this equation, your shop personnel, as their input is invaluable to keeping you up and running in a profitable, customer-satisfying scenario. The author welcomes questions, comments and additional input from readers. Please contact Preben Hansen at 847-749-0633 or phansen@platinumtooling.com. Mr. Hansen has over 30 years in tooling and is considered a leading authority on the topic in the North American machine tool market.

|

Technical Support BlogAt Next Generation Tool we often run into many of the same technical questions from different customers. This section should answer many of your most common questions.

We set up this special blog for the most commonly asked questions and machinist data tables for your easy reference. If you've got a question that's not answered here, then just send us a quick note via email or reach one of us on our CONTACTS page here on the website. AuthorshipOur technical section is written by several different people. Sometimes, it's from our team here at Next Generation Tooling & at other times it's by one of the innovative manufacturer's we represent in California and Nevada. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About

|

© 2024 Next Generation Tooling, LLC.

All Rights Reserved Created by Rapid Production Marketing

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed