|

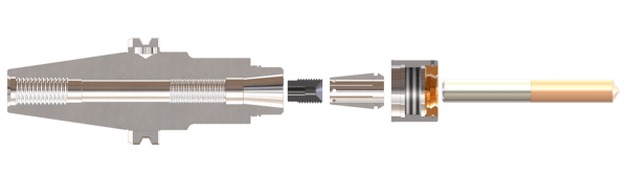

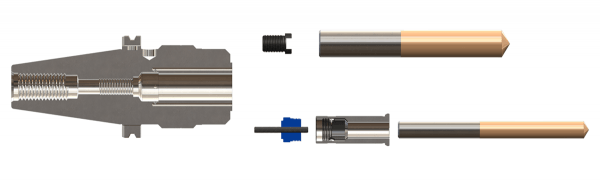

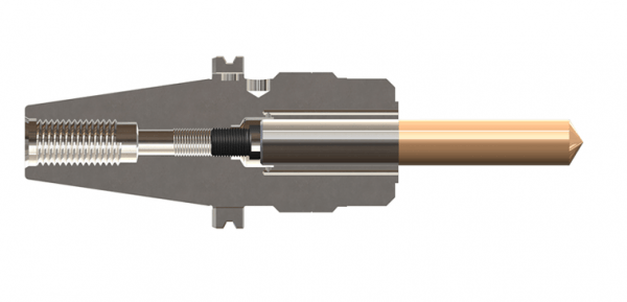

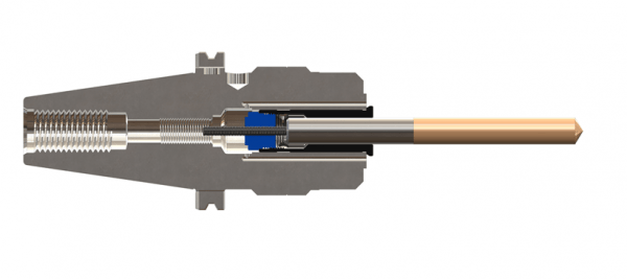

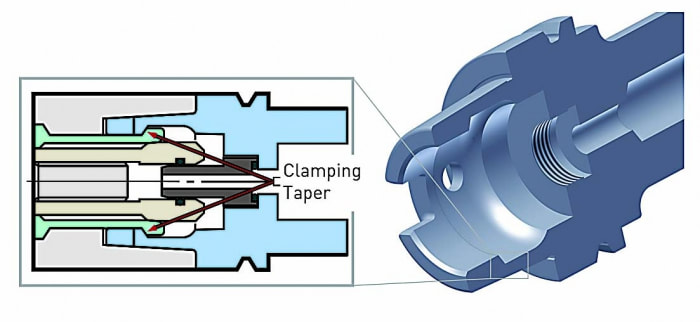

As the title implies adjusting screws, also known as back-up screws, stop screws and preset screws, are not just a simple set screw. They are a screw with a purpose--three actually. The first is to provide a fixed stop for a cutting tool to rest against during tool changes. This allows an operator to save time as they do not have to pull out a ruler, setting jig, etc. to reassemble the cutter into a holder. A secondary purpose of the adjusting screw is to assist the tool holder in keeping the cutter from being pushed up into the holder if the cutting loads increase to the point where the tool may slip up into the holder. The third is to offer sealing for coolant-through tools. 1. Expected repeatability of cutting tool lengthWhen an old cutter is swapped out and a new one put in its place, the repeatability of this process will vary based on a few parameters such as cleanliness and the OEM cutting tool overall length tolerances. Cleaning the clamping bore or collet of a holder provides better runout repeatability which should be old news to everyone, but if old coolant and contaminants are not removed, they would get jammed between the end face of the shank and the adjusting screw, affecting the length setting. Cutting tool overall length tolerances may also vary from one OEM to another. We have seen them range from ±.3mm to ±.5mm (±.012” to ±.019”). Others may be tighter or looser. Most modern machining centers come with tool length offset measurement systems which will provide the final precise gage length of a tool assembly. With the rough position provided by the adjusting screw, the machine operator can continue working and does not need to worry about tool clearances and stick outs. 2. Forms of adjusting screwsThe clamping mechanism of the holder also affects the length repeatability. Both hydraulic chucks and milling chucks are radial clamping systems, whereas a tapered collet is drawn down into a taper by a threaded nut. This draw down causes the cutter to be drawn down as well. For this we have two types of adjusting screws: HMA/HDA solid type and NBA rubberized type. The solid type is a one-piece steel construction part, whereas the rubberized type has a rubber padded conical pocket that absorbs the axial travel of the cutter shank as the collet is clamped. 3. Option for adjustable reduction sleeves for MEGA DS/HMCMilling chucks also have a second type of adjustment screw option that can be built into the back end of a reduction sleeve. As cutting tool diameters get smaller, the length of the shank also gets shorter. As such, the end face of the shank may not reach the HMA adjusting screw when installed it the body of the holder. The AC Type Collet adjuster screws into the back end of the reduction sleeve where the shank the tool can easily be reached. 4. Warning on holders that cannot support adjusting screwsIt is always recommended to consult the tool holder catalog or technical documentation to ensure that a holder can support an adjusting screw. Some holders are very short or have very deep internal features that may not allow for the use of any adjusting screw. In those cases, a depth setting ring or collar on the shank of the cutting tool may be an acceptable alternative.

Caution should be used on shrink-fit holders. Thermal expansion/contraction occurs in all three axes, so as the body of a shrink-fit holder cools down it will draw the cutter down jamming onto the adjusting screw. This could lead to damage to the screw, the holder or the cutter.

0 Comments

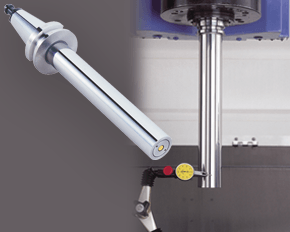

The four critical requirements for tool holders are clamping force, concentricity, rigidity, and balance for high-spindle speeds. When these factors are dialed in just right, there’s nearly no chance of holder error and considerable cost reduction is achieved thanks to longer tool life and reduction of down-time due to tool changes. Easier said than done, our experts shared some of their best, quick-hitting advice for top tool holder performance in different situations. 1. Balance holders as a complete assembly Long-reach milling has some unique demands; when setting up this type of job, always balance tool holders as a complete assembly. While many tooling providers pre-balance their holders at the factory, it’s often inadequate, especially for long-reach applications. 2. Holder damage can go from bad to worse quickly Wear and tear on holders can be costly in the end, but there are ways to protect against it. Inspect and care for your holders. Trauma on a holder or spindle—dings, scratches, gouges, etc.—can magnify quickly. One bad holder can spread its problems like an illness. If you’re seeing disruptions like these on your holders, get them out of the rotation. 3. The rule of thumb on holder dimensions Looking for affordable ways to avoid vibration? Start by opting for a holder with a combination of the largest diameter and shortest length possible. 4. Rigidity can harm tapping operations What many don’t realize about tapping operations is that a perceived strength of collet chucks—their rigidity—can actually be detrimental. Rigidity does very little to counteract the dramatic thrust loads imposed on the tap and part, exacerbating the already difficult challenge of weathering the stop/reverse and maintaining synchronization. 5. Balancing is crucial to five-axis machining Five-axis machining introduces a whole new set of tooling challenges. While important in any type of machine, balance may be of most importance in full five-axis work. A well-balanced holder helps ensure the cutting edge of the end mill must be consistently engaged with the material in order to prevent chatter and poor surface finish quality. 6. Consider spindle speed requirements when choosing between shrink-fit and hydraulic holders If you have to choose between shrink-fit and hydraulic holders in a long-reach application, consider the spindle speed required. If a hydraulic chuck exceeds its rated RPM, fluid is pulled away from the holder’s internal gripping gland, causing loss of clamping force. But when used within its recommended operating range, a hydraulic tool holder offers superior runout and repeatability. On average, a good shrink-fit holder has about 0.0003-inch runout, while a hydraulic chuck offers 0.0001 inch or better. 7. Don’t overlook the tool’s effect on holder performance The cutting tool affects holding ability more than most machinists and engineers realize:

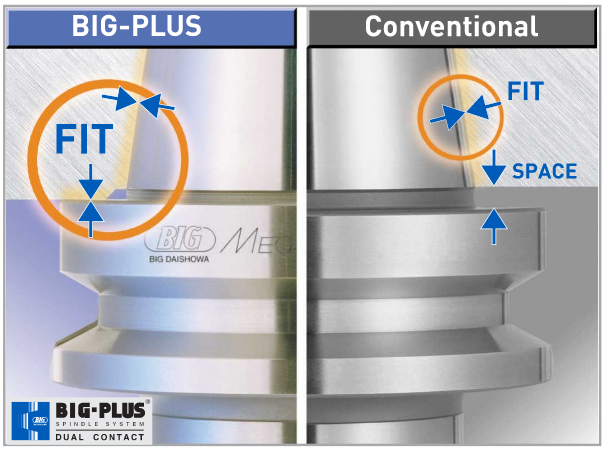

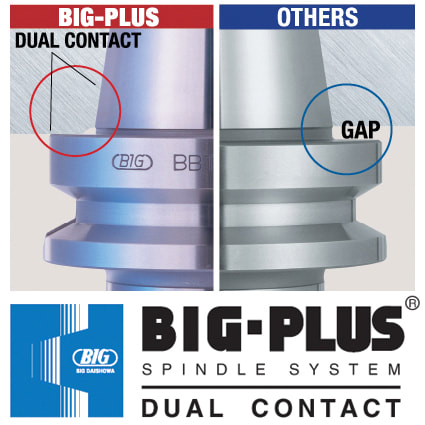

8. Not all dual-contact tooling is the same Anyone in the market for BIG-PLUS dual-contact tooling should consider this simple statement: Only a licensed supplier of BIG-PLUS has master gages that are traceable to the BIG grand master gages and have the dimensions and tolerances provided to make holders right. Everyone else is guessing and using a sample BIG-PLUS tool holder as their own master gage—a practice that any quality expert will advise against. Look for the marking: “BIG-PLUS Spindle System-License BIG DAISHOWA SEIKI.” 9. You may have a BIG-PLUS spindle and not even know it You’d be surprised how often we hear from our certified regrinders or engineers in the field about folks that didn’t realize their machine had a BIG-PLUS spindle—the message can get lost in the supply chain or during the sales process. The easiest way to know if an interface is BIG-PLUS is to place a standard tool into the spindle and see how much of a gap there is between the tool holder flange face and spindle face. Without BIG-PLUS, the standard gap should be visible, or about 0.12 in. If it is BIG-PLUS, the gap is half of this amount, or only 0.06 in. These values change depending on 30 taper, 40 taper or 50 taper sizes, but the gap is visibly less than usual. 10. Use positive offsets during holder setup It may be how it’s traditionally been done but touching off holder assemblies in each machine to establish negative tool offsets based on the zero-point surface—the vise, machine table, workpiece, etc.—is not the most efficient process. We think the choice is pretty clear: adapting machines to a single presetter so they can receive positive gage lengths is superior to using all types of machine-specific negative offsets.

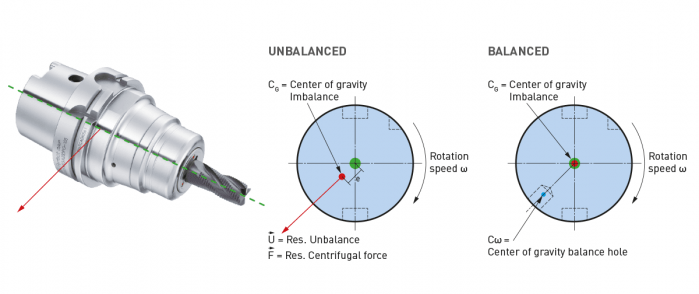

This is a change to “the way things have always been done” that can be met with some resistance, but in the grand scheme of things, it’s a relatively small and simple step that makes life much easier. It’s a relatively low-cost opportunity to introduce more standardization of holder setup to the shop floor. Holders are the bridge between the machine and the part. That’s a lot of pressure—literally and figuratively. It’s important to select, care for and use holders carefully from the day they are purchased until they’re tossed into the recycling bin. From collet chucks to coolant inducers, BIG KAISER is North America’s source for standard-bearing tool holders that guarantees high performance. Explore the full lineup. A machine’s spindle is one of the key links in the machining chain. In other words, if there are irregularities inside or at the face, they can show up on your part. It makes regular inspection and spindle maintenance critical to getting the most out of your equipment and maintain process efficiency. These three accessories, the Dyna Contact Taper Gage, the Dyna Test Bar and the Dyna Force Measurement Tool, can help you perform this maintenance easily without eating into valuable spindle time. Dyna Contact Taper Gage

Dyna Test Bar

With the help of a dial indicator, you can uncover any runout while safely spinning the spindle at a very low RPM and verify the parallelism of Z-axis motion. Dyna Force Measurement Tool

The Dyna Force measurement tool provides a precise digital reading that reveals reduction in retention force in increments of 0.1kN. If you would like a demonstration for any of these tools contact us or set up an appointment for one of our Next Generation Tooling engineers to visit you!

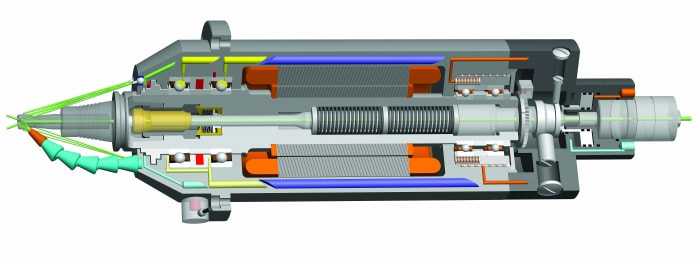

A guest blog from BIG KAISER. High-speed machining started getting popular in the ‘90s, especially in aerospace where they replaced fabricating processes with machining monolithic parts like wing struts from billets. Machine tools capable of spinning cutting tools at tens of thousands of RPM made it easier to produce these parts quickly. Like machines, holders adapted. The centrifugal forces they had to manage in order to keep tools cutting correctly became extreme. The toolholding systems available at that time were found not to be as effective as the shallower 1-to-10 taper ratio of the German hollow taper shank, hohl shaft kegel (HSK) in German. The HSK has since been standardized to ISO specifications (12164-1, -2). HSK is now available in several sizes and forms to fit with small to large machines. For the most part, the market has settled on the form A for general milling. It has been adopted in Japan, North America and Europe and is truly one of the only worldwide-side toolholder standards. Form E or F is for high-speed machining. The forms have different features depending on the standard they follow. In the end, to achieve efficient tool life, proper finish and productivity in high-speed work, holders need to be as rigid, compact and short as possible to keep the whole assembly stable. What to know when choosing a high-speed tool holder

When it comes to balancing holders, the quality G2.5 is widely used in the industry and is described in the ISO 1940-1 (issued in 2003) standard. However, this quality class is often over-specified and is in many cases not economically or technically feasible, especially when applied to smaller and lighter tools. Standards often applied to tools are more suited for rigid rotors and are practical in a broader use for balancing.

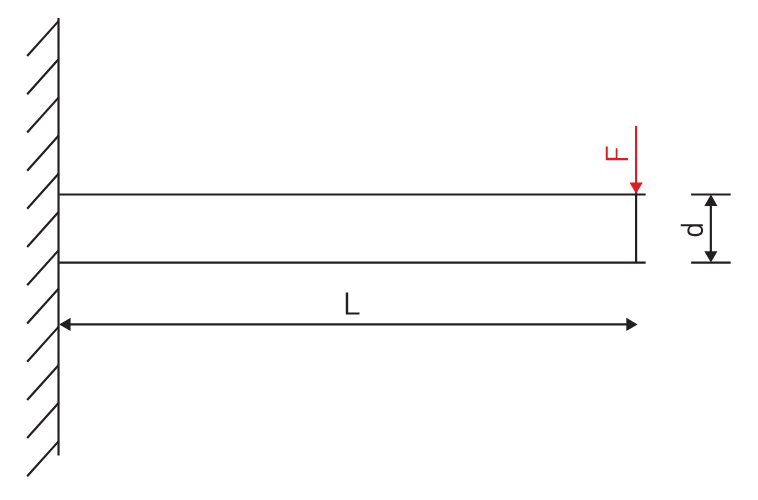

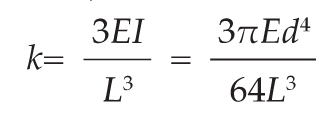

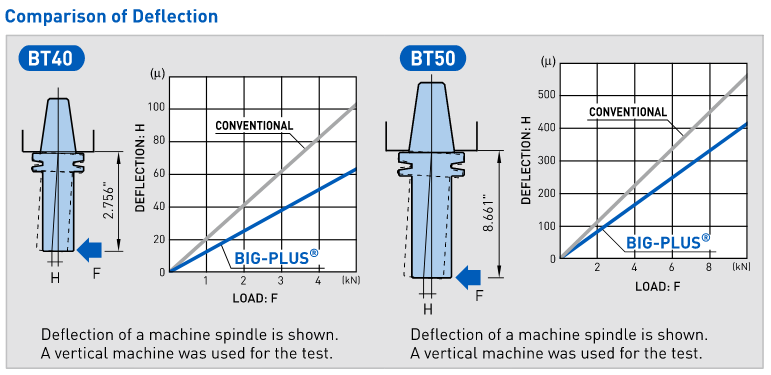

However, it cannot be applied to a complete system of spindles, tool holders and tools adequately and within technical constraints. For example, a tool to be compliant will have to be balanced to less than 1 gmm/kg at a speed of 25,000 rpm, which in turn corresponds to a mass eccentricity of less than 1 μm. This allowable tolerance is less than the interchange accuracy for even HSK, essentially negating all the costs and time for balancing the tool to such a strict tolerance. For this reason, all BIG KAISER tool holders are balanced according ISO 16084 (issued in 2017) specifically developed for rotating tool systems. ISO 16084 focuses on the interaction between spindle and tool factoring in the allowable load on the spindle bearings generated by the tool’s imbalance. This load must not exceed one percent of the dynamic load capacity of the spindle bearings. According to ISO 16084, the allowable unbalance tolerance is specified in [gmm] and is not expressed using a special quality grade [G]. In conclusion, BIG KAISER does not indicate any G-values for balancing quality, but rather the maximum rotational speeds of the individual tool holder. The BIG Kiaser MEGA holder program includes a variety of styles that can be used up to 40,000 RPM. They guarantee 100 percent concentricity and runout accuracy down to .00004" at the nose. They are built specifically to withstand speed and forces required in today’s high-throughput environment. For more information on BIG KAISER's approach to balancing tool holders, click here. To learn more about our high-performance tool holders here. Spindles and tool holders are in a constant battle with the forces of nature, with this battle becoming more and more difficult with heavier cuts and longer projections. Chattering and deflection have always been the bane of machinists’ existence, so much so that the sight of a long and slender toolholder will immediately cause goosebumps. If you understand why a long tool holder behaves the way it does, you’ll know that there are ways to fight back against this bending. Every machinist knows that short and stubby holders are more resistant to deflection than long and slender holders. You’ve also probably heard that, if possible, you’ll want most of your cutting forces to be axial rather than radial. Not only does this fight chatter in operations like boring, but your spindle also is better equipped to handle loads in this axis. However, these options aren’t always going to be on the table, especially in unavoidable long-reach situations and many milling operations. In this constant battle with tool deflection, much time and effort has been spent designing shorter holders, stiffer tools, and clever anti-vibration geometry and materials. But oftentimes, the body diameter(s) of the holder can be overlooked as a means of increasing rigidity, especially in situations where it is all you have to work with. This is a serious shame, as you’ll soon discover. The concept of dual-contact technology has been around for years, existing in many different forms but always with the same goal of capitalizing on this untapped potential of rigidity. For those who don’t know, dual contact refers to the shank contacting the spindle taper and the spindle face simultaneously. Oftentimes, the solution involved ex post facto alterations to the spindle or tool holder, such as using ground spacers or shims to close the gap, for example. In other words, there was no standard solution, and if you wanted dual contact, you would have to be prepared to spend time and money either buying modified tool holders or modifying them yourself to adapt them to your spindle. BIG-PLUS emerged as a solution to this issue. Essentially, both the spindle and tool holder were ground to precise specifications so that they closed the gap between spindle face and flange in unison (while depending on very small elastic deformation in the spindle). What this meant is that operators were able to confidently switch BIG-PLUS tooling in and out of a BIG-PLUS spindle and achieve guaranteed dual contact. Not only that, but standard tooling could still be used in a BIG-PLUS spindle if necessary, and vice versa. Though not technically an international standard, it’s been adopted by many machine tool builders because of the clear performance improvements and simplicity. In fact, BIG-PLUS spindles come standard on more machines than you would think. We often come across operators that have machines with BIG-PLUS spindles and don’t even realize it. How exactly does dual contact help with tool rigidity? The torque (or moment) exerted by the cutting forces is maximized at the point where the holder and spindle meet, the base of the tool holder. With standard CAT40 tool holders, this would be the gage line diameter. When the holder contacts the spindle face via BIG-PLUS, the effective diameter would be the larger diameter of the v-flange, since this is the new anchoring point of the holder and spindle. So, you are beefing up the diameter at the point where the reactionary force is greatest. It’s not too much of a leap to conclude that a larger effective diameter will give you more rigidity. That being said, you may still be asking yourself: does such a seemingly small increase in diameter really make a difference? To understand the effect of BIG-PLUS, you must understand the physics behind it. Imagine a simple scenario in which a tool holder is represented by a cylindrical bar that is fixed at one end and free-floating at the other. In other words, a cantilever beam. If you think about it, this is essentially what a tool holder becomes once it’s secure in the spindle. Now, let’s introduce a radial force F that acts downward at the suspended end of the bar, which represents a cutting force you would encounter when milling or boring, for example. The bar, as you might expect, will want to bend downward. It’s similar to how a diving board bends when someone stands at the end, though less exaggerated. It’s possible to predict the amount of deflection (or inversely, bending stiffness) at the end of this hypothetical bar if you know its length, diameter and material. The expression below represents the stiffness k at the end of the bar where d=diameter, L=Length and E=Modulus of Elasticity I won’t ask you to do any math here, I just want you to look at the equation. We can see that increasing d will increase the value of k, while increasing L will decrease the value of k, since it’s in the denominator of the equation. This certainly makes sense if you think about it: a short and squat bar (large d, small L) will be more rigid than a long and slender bar (small d, large L). Something interesting to note is that d is raised to the 4th power, while L is only raised to the 3rd power. Diameter affects rigidity an entire order of magnitude more than the length does. This is where the power of BIG-PLUS comes from and is why a small increase in diameter can have such a powerful effect on performance.  For a CAT40 tool holder, the gage line diameter is Ø44.45 mm and the flange diameter is Ø63.5 mm. Let’s imagine two bars of identical length and material, so L and E remain unchanged. One bar has a diameter of Ø44.45 mm (standard CAT40) and the other has Ø63.5 mm (BIG-PLUS CAT40). If you were to plug these values into the above equation for comparison, you would find that the BIG-PLUS holder results in a k value that is around 4 times greater than the standard bar. Based on this comparison, you could say that a BIG-PLUS holder is 4 times as rigid as an identical standard CAT40 holder, because it is 4 times as resistant to deflection. Think of the tool life and surface finish improvements you would see with a tool that is 4 times more rigid, not to mention the reduction in fretting and potential for reduced cycle time. You would get similar results if you were to make the same comparison for CAT50, BT40, BT30, etc. If you’re still not convinced, we can also compare the rigidity in this way: Let’s say there is a Ø63.5 mm BIG-PLUS CAT40 bar of some arbitrary length. One of our more common gage lengths is 105 mm, or just over 4 inches, so let’s use it as an example. You’re probably wondering, at what length would a comparable standard CAT40 holder have an equal stiffness? If we take our stiffness expression and set it equal to itself (one side representing BIG-PLUS, the other non BIG-PLUS), we can plug in this BIG-PLUS holder length and our known diameters to find our unknown non-BIG PLUS length: What does this mean? A BIG-PLUS holder of around 4 inches or 105 mm in length will have equal rigidity to a standard CAT40 holder of around 2.5 inches or 65 mm in length. Any experienced machinist will know quite well the difference in rigidity between a 4-inch long holder and a 2.5-inch long holder.

If this is true, we can say that implementing BIG-PLUS is equivalent to a 40% reduction in length in terms of rigidity. Theoretically, a BIG-PLUS tool holder will behave like a standard tool holder that is nearly half of its length! Obviously, we’ve used simple and idealized cases here to represent the complicated and dynamic world of metal cutting. Tool holders, of course, don’t have uniform body diameters or materials and the cutting forces usually aren’t acting in one direction in a constant and predictable way. If our holder necks up and down to different body diameters along its length, which is realistically what happens, each of these sections would be its own microcosm of “beam” that would influence the overall behavior (at that point, finite element analysis on a computer becomes the only practical way to predict behavior). So, will the advantage of BIG-PLUS really be as dramatic as our hand-calculated classical beam theory suggests? Probably not, but it depends on the tool holder/tool. Most cases will follow our simple model quite closely in practice; others not so much. If nothing else, we’ve demonstrated how dramatically the flange contact of BIG-PLUS can influence rigidity, at least in a purely mathematical sense. As if you needed any more reasons to be on the BIG-PLUS bandwagon besides increased rigidity, you will also eliminate Z-axis movement at high speeds, improve ATC repeatability and decrease fretting. This means that you will take heavier cuts, scrap less parts, and increase tool and spindle life. BIG-PLUS isn’t a new idea by any means, but with a proven track record of tackling tough jobs, it’s hard to imagine working in a modern machine shop and not taking advantage of what it has to offer. If you’re still not convinced, we can also compare the rigidity in this way: Let’s say there is a Ø63.5 mm BIG-PLUS CAT40 bar of some arbitrary length. One of our more common gage lengths is 105 mm, or just over 4 inches, so let’s use it as an example. You’re probably wondering, at what length would a comparable standard CAT40 holder have an equal stiffness? If we take our stiffness expression and set it equal to itself (one side representing BIG-PLUS, the other non BIG-PLUS), we can plug in this BIG-PLUS holder length and our known diameters to find our unknown non-BIG PLUS length: Shrink-fit and hydraulic holders are both useful in low clearance, tight work envelopes found in moldmaking and multi-axis machining applications. When deciding which one to use, their differences will guide your choice. Here are some of the fundamental contrasts to help you decide which holder type is best for your work.  Hydraulic holders (shown here) and shrink-fit holders share a middle-of-the-road gripping strength: about half that of a milling chuck and about double that of collet chucks. The superior vibration control of hydraulic chucks makes them good choices for finish milling, reaming and drilling work. While they may not be as precise, the rigidity of shrink-fit holders makes them effective in moderate to heavy milling work where clearance is an issue, and in many high speed scenarios. Shrink-fit and hydraulic holders are especially useful in low clearance, tight work envelopes because of their relatively slim design. This has made them effective in moldmaking applications and more coveted since the widespread adoption of multi-axis machinery. Hydraulic and shrink-fit holders also share a middle-of-the-road gripping strength: about half that of a milling chuck and about double that of collet chucks. These similarities are why we’re taking the time to compare the two. When it comes to deciding between one or the other, it’s the differences that will guide the choice. So let’s dig into some of the fundamental contrasts that may help you decide which holder type is best for you and your work. Initial InvestmentWhen it comes to the holders themselves, shrink-fit is generally a slightly lower cost. The delicate hydraulic clamping systems built into the holders add cost when compared to the simple and solid bodies of shrink-fit holders. Where the major difference lies is in the equipment needed to heat the shrink-fit holders. When heated to the proper temperature, the resulting growth of the ID allows the tool to be slipped into the bore. Once cooled, the holder expands, gripping the tool. This process, especially the induction heating, involves cost. Shrink-fit heating systems start at around $5,000 and go up from there. They also require fairly significant power, adding a slight ongoing expense. MaintenanceIf you want to see a full return on your shrink-fit investment and then some, maintenance is critical. When dealing with temperatures that can approach 600 deg F, the stakes are heightened. This is why we recommend using dry cutting tools without oil on them. From there, diligent attention must be paid to the cleanliness of holder bores and tool shanks. Any contamination will be baked onto the metal and progressively deteriorate performance. When it comes to hydraulic chucks, maintenance is straightforward as long as the hydraulic chamber stays sealed. To ensure the hydraulic system performs consistently, we recommend using test pins to gauge its force over time. Training, Handling and Safety Hydraulic chucks are infinitely simple. A turn of a wrench locks the tool in place. When it comes to shrink-fit systems, there are a few more factors to consider when getting the team up to speed, including safety considerations. Aside from the operators who handle the tooling and heating system directly, others on the floor need to be made aware of the risk of burns. Heating stations are usually benchtop arrangements because of the power requirements. This means hot metal will need to be transported across the floor in one form or another. Another training consideration is that tools can be overcooked, so to speak. This will cause permanent damage that harms performance. Operators must understand, know how to prevent and diagnose this. SetupAs mentioned earlier, hydraulic chucks use a simple wrench to lock in the tool. Tools can also be swapped at the machine or offline. When it comes to shrink-fit setups, they must be done exclusively offline where the heating and cooling can be powered. Most heating cycles can be as fast as 15 seconds. Cooling can take several minutes, even with assistance like air. Having extra compatible holders is a viable solution to speed concerns, if you’re comfortable with the additional investment. All that being said, there are significant time-saving opportunities to be found setting up tools offline. We believe strongly in tool measuring systems and recommend offline setup when and where applicable. VibrationHydraulic chucks have two specific advantages in terms of vibration and accuracy. The first is that shrink-fit tools and holders are dependent on the heating and cooling processes being consistent. This brings us back to the maintenance section above; the slightest imperfection in the holder bore, not to mention the natural inconsistencies in the heating and cooling processes, can be multiplied at the cutting edge in the form of vibration or runout. There is also the chance of some variation from operator to operator. Hydraulic chucks are less reliant on these variables and their production is imminently consistent. Once a master bore is established during manufacturing and assembly, it’s a repeatable process over thousands of cycles. This translates to consistent clamping tolerances and forces over the life of the holder. The second advantage is the natural damping characteristics that hydraulics provide. That’s not to say shrink-fit holders are ineffective in terms of vibration management. Their runout is five times better than side-lock holders. Roughing and FinishingThat brings us to some application talk. While they may not be as precise, shrink-fit holders’ rigidity makes them effective in moderate to heavy milling work where clearance is an issue, and in many high speed scenarios. The superior vibration control of hydraulic chucks makes them good choices for finish milling, reaming and drilling work. Roughing and FinishingUp to this point, you may think I’m an advocate of hydraulic chucks over shrink-fit holders, but that’s not the case. We offer both products. In fact, shrink-fit holders are fundamentally the perfect tool holder. From an engineering perspective, there are no moving parts, no additional components, they use the properties of the holder itself to grip the tool and they’re symmetrically round. But as we all know, a manufacturing floor is not a perfect environment. Variables must be considered when choosing equipment.

Should the choice between hydraulic chucks and shrink-fit holders come up, the factors discussed here will help guide your choice. Below are excerpts from a Cutting Tool Engineering article by the same title. To read the entire article please click HERE.  Author Kip Hanson, Contributing Editor, Cutting Tool Engineering (520) 548-7328 khanson@jwr.com Kip Hanson is a contributing editor for Cutting Tool Engineering magazine. Originally Published: September 12, 2017 - 3:00pm Shopping for a machining center was simpler when buyers had only two basic spindle choices: CAT or BT. Both of these “steep tapers” have an angle of 3.5 in./ft., or 7" in 24" (7/24), and are based on the 1927 patent by Kearney & Trecker Corp., Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Co. and Cincinnati Milling Machine Co. With the development of automatic toolchangers in the late 1960s, machine tool builders in Japan modified the patented design and invented the BT standard. In the 1970s, tractor manufacturer Caterpillar Inc., Peoria, Ill., changed things again with a flange design now known as CAT, or V-flange. “Sticking” TogetherDuring the late ’80s, machine tool builders began offering vertical and horizontal CNC mills with spindle speeds higher than the 6,000 to 8,000 rpm common at the time. As rpm increased, so did problems with steep-taper toolholders. Chief among them is the tendency for the mating spindle and toolholder tapers to stick together. This is caused by the expansion of the spindle housing at high speeds, which allows the toolholder to be pulled upward into the spindle taper, jamming it in place. HSK spindles, like the one shown in the illustration below, offer advantages steep-taper styles can't. One way to eliminate this problem is by extending the toolholder flange upward, thus creating a hard stop against the spindle face and preventing further Z-axis movement. This is the approach taken by BIG KAISER Precision Tooling Inc., Hoffman Estates, Ill. Jack Burley, vice president of sales and engineering, said the BIG-PLUS system—developed in 1992 by BIG Daishowa Seiki Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan—relies on a bit of elastic deformation in the spindle to provide dual points of toolholder contact at its face and taper, eliminating upward holder movement as the spindle expands. He said it’s also more rigid, with tests showing that the deflection on a CV40 BIG-PLUS toolholder measured at 70mm (2.755") from the spindle face is only 60µm (0.002") when subjected to 500kg (1,102 lbs.) of radial force, roughly half that of a traditional V-flange toolholder. “There are now roughly 150 machine builders that either offer BIG-PLUS or have it as a standard,” Burley said. “The beauty of the system is that it can use either standard toolholders or BIG-PLUS interchangeably. So for drilling and reaming work, you can use a conventional collet chuck, but for heavy milling cuts or profiling operations at higher spindle speeds, BIG-PLUS improves accuracy and tool life.” Revving UpBurley does not recommend BIG-PLUS for older machines that have never seen these toolholders, because CAT and BT taper-only contact holders tend to bellmouth the spindle over time, leading to undesirable results. BIG-PLUS, like any dual-contact toolholder, requires particular attention to cleanliness, as chips caught between the spindle face and the toolholder can cause serious problems. He also recommends staying below 30,000 rpm when using 40-taper holders, noting that higher speeds are better handled by HSK spindles and holders. Keep It CleanBill Popoli, president of IBAG North America, North Haven, Conn., said the company started building steep-taper spindles in the late ’80s, but 95 percent of its work has since transitioned to HSK spindles. As mentioned earlier, the extreme accuracy needed to guarantee near-simultaneous contact between the spindle face and taper is challenging, requiring micron-level tolerances in toolholder and spindle alike. These requirements were impossible to meet when steep taper was first developed, Popoli said, resulting in looser standards overall for CAT and BT spindles than the ones applied to HSK spindles and toolholders. Because of this, purchasing an HSK or equivalent toolholder automatically makes one “part of the club” when it comes to balance, accuracy, repeatability and tool life. That’s not to say, however, that shops firmly married to steep tapers should settle for less. Popoli recommends purchasing the highest-quality tooling possible and paying close attention to the stated tolerance.

Always stay below 20,000 rpm with 40-taper holders, and reach no more than 30,000 rpm with 30-taper ones. Use balanced holders and high-quality retention knobs that have been properly torqued—otherwise distortion at the small end of the taper may occur. And whatever the taper type, keep the spindle and toolholder clean at all times. Bob Freitag agreed. The manager of application engineering at Minneapolis-based metalworking products and services provider Productivity Inc. said the lines are evenly split between traditional 40- and 50-taper CAT or BT tooling (much of which is BIG-PLUS) and HSK. “It really depends on the application,” Freitag said. “Most of our die and mold machines in the 20,000- to 30,000-rpm range will have an HSK63A or HSK63F. When you get up around 45,000 rpm, you’re probably looking at an HSK32. But in horizontal machining centers and lower-rpm, high-torque verticals, you’ll see mostly steep tapers, as this is generally preferred for deep depths of cut and lower feed rates, where you’re removing a lot of material at once.” For shops that want to make the leap to an HSK machine but are leery of investing in new toolholders, Freitag advised: “Anytime you buy a new machine, you should buy new toolholders to go with it. If not, the imperfections of the old toolholders will soon transfer themselves to the spindle on the new machine.” |

Technical Support BlogAt Next Generation Tool we often run into many of the same technical questions from different customers. This section should answer many of your most common questions.

We set up this special blog for the most commonly asked questions and machinist data tables for your easy reference. If you've got a question that's not answered here, then just send us a quick note via email or reach one of us on our CONTACTS page here on the website. AuthorshipOur technical section is written by several different people. Sometimes, it's from our team here at Next Generation Tooling & at other times it's by one of the innovative manufacturer's we represent in California and Nevada. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

About

|

© 2024 Next Generation Tooling, LLC.

All Rights Reserved Created by Rapid Production Marketing

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed