|

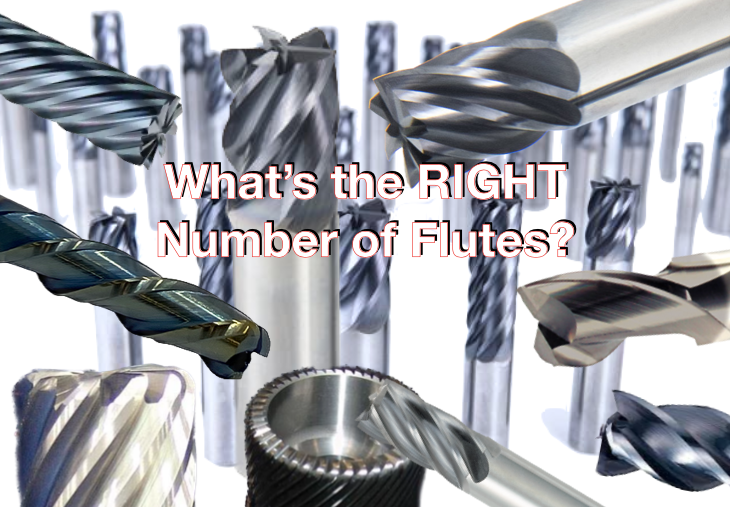

The number of flutes on a carbide end mill significantly influences its performance across various machining applications. How many flutes do you need? The simple answer: It depends. Obviously there are a quite a number of other factors that impact an end mills performance such as helix angel, edge prep, gullet depth and radius. We can't tackle everything in this article, but hopefully this helps you get a better understanding of why there are different numbers of flutes on end mills. Below is an overview of the advantages and disadvantages associated with end mills featuring different flute counts, along with recommendations for materials based on ISO 513 categories (P, M, K, N, S, H) Single Flute End Mills

2-Flute End Mills

3-Flute End Mills

4-Flute End Mills

5-Flute End Mills

6-Flute End Mills

7-Flute End Mills

8-Flute End Mills

0-Flute End Mills

Advantages of Higher Flute Counts in |

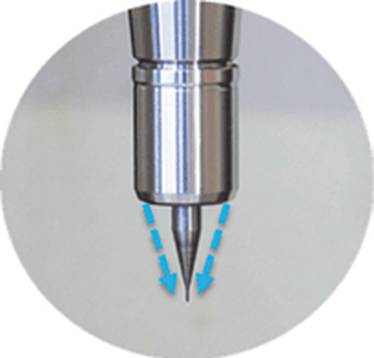

| Much of this burden falls on the holder. Balance doesn’t change as spindle speed increases, however the forces it creates increase exponentially alongside speed. The impacting results appear quickly in micromachining. When runout occurs, the edge most affected takes over the bulk of the cutting. Uneven wear causes the tool to fail more quickly than if the tool rotates about the centerline as intended. In one customer application, we found that drilling into a steel workpiece 0.590" deep with a 0.118" diameter carbide drill in a holder with 0.00008" runout accuracy produced 2,300 holes. |

Holder attributes that can boost production include symmetrical design, a perfectly concentric collapse of the collet around the cutter, and a ball-bearing raceway nut with precision-ground threads.

While these characteristics are good rules of thumb, things change fast in this field and, like our customers, we must adapt as trends emerge.

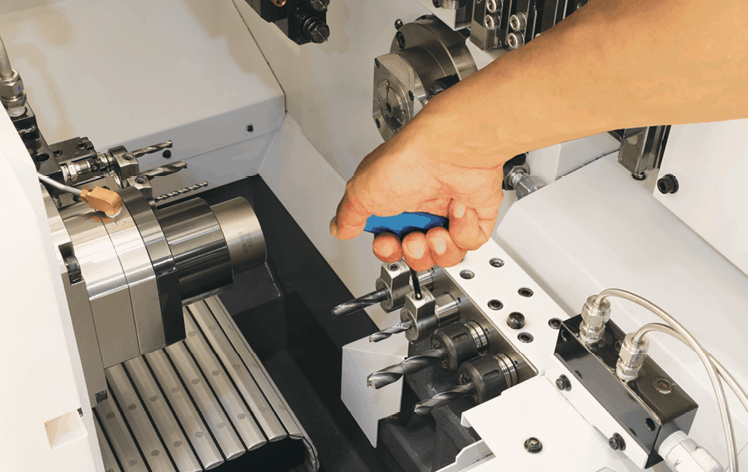

Batch sizes are getting smaller. Bone screws, for example, were typically run on multi-axis, Swiss-type lathes where the same tools and programs ran for days at a time. Traditionally, prototyping in this arrangement was not an option because of the complexity and time involved in programming and setup. Today’s need for customized sizes demands flexibility and quick changeover to remain productive.

We are investing a large portion of our research and development (R&D) in tackling this challenge. We are working on hydro-clamping tool holder systems that could make the decades-long approach of using ER collets obsolete. It would make it possible, for example, to perform a simple drill change on a gang slide in seconds.

Another trend in medical manufacturing being driven by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is clean machining without the use of water-soluble coolants.

| Super-chilled CO2 or cryogenic machining with liquid nitrogen are considered possible replacements. Protecting small holder parts at the nose from coolant has always been a concern, but using gas requires more attention for holders to be effective. |

- Holders that remain completely sealed to outside atmosphere

- Very small delivery holes in collet faces or clamping nuts that properly restrict gas flow

Tool considerations also must be taken into account to keep up with the demanding medical field. Better results often cannot be achieved by simply increasing spindle speeds or using smaller tools; a deeper understanding of cutters is necessary.

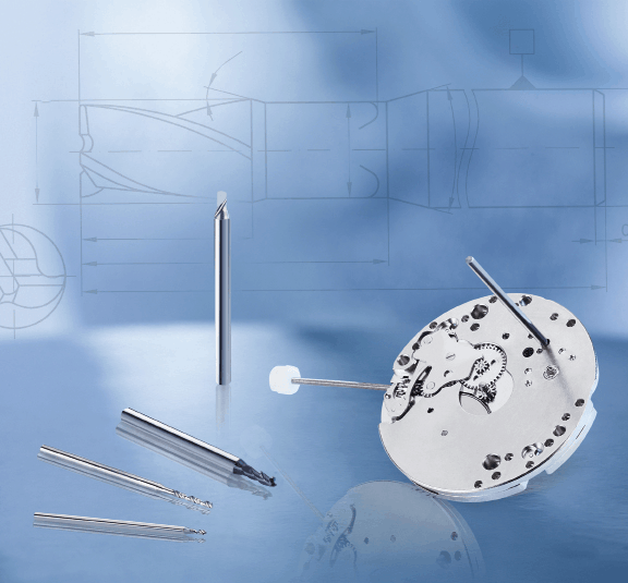

We consider tools with diameters <3mm to be micro tools. These aren’t simply smaller versions of their macro counterparts. They have geometric considerations all their own. For example, the 1mm Sphinx drill can run at 80xD. But this is only possible because the cylindrical shaping extends further down the tool, closer to the tip, to facilitate pecking and maintain strength.

Tool carbide should be ultra-fine grain (nano or submicron grain size) to ensure high abrasion resistance and good toughness. Coatings are valuable too, but it’s important to understand how coatings can negatively impact micro tool performance. Micro tools have extremely fine surface finishes and sharp cutting edges. Coatings can fill in valuable space – a flute on a drill, for example – needed for proper chip evacuation, which is critical in these applications.

Coatings must be ultra-thin (<1µm) and smooth; our experience shows that misapplied coatings result in poor tool life due to breakage; the coating reduces cutting edge sharpness, increasing torque force on the drill. When coating is necessary, consult with the cutting tool manufacturer to provide this directly.

Chips and small tooling naturally do not get along well. Compensating for low spindle speeds with tools that have more flutes support an ideal feed rate, but chip evacuation may suffer. Determining the appropriate chip load – as close to the cutting edge as possible – allows operations at the highest possible spindle speed, accelerating the cycle and improving surface finish.

Optimal conditions exist when the chip load is relatively equal to the cutting edge radius.

Many micro end mills are designed so the cutting edge radius has a positive rake angle to create a shearing action. A chip load less than the cutting edge radius often results in a negative rake angle where the tool rubs rather than cuts. This increases the force required and generates more heat which can result in built-up edges and poor tool life. A chip load significantly bigger than the cutting edge radius often leads to premature failure because the tool is not robust enough to withstand such forces.

Micromachining requires machine tools with very high sensitivity, fine resolution in the feed axis, and very precise spindles capable of high speed with low dynamic runout. For micro-drilling operations, specialized micro machines are best.

Micro milling machines are suited for small tools and small workpieces. They are characterized by spindle speeds faster than 50,000rpm using small HSK tool holders such as HSK-E32, E25, or E20. With the right holder, tool runout can be controlled to less than 1µm (0.000040") at the cutting edge, ensuring sub-micron accuracy.

In medical micromachining, understanding each piece of the equipment puzzle is critical. It’s also important not to make assumptions based on other tools or parts you may have worked with, especially in more standard sizes. Invest the right time and energy in gearing up for the next medical job and you’ll get more parts done right faster.

| An argument can be made for balancing almost every tool put in a machine. In the world of rotating tools, small changes to an assembly, like a new cutting tool, collet, nut or retention knob, can put an assembly out of tolerance. Therefore, it stands to reason that any unbalance could translate to the part, tooling and/or machine spindle in harmful ways. You’ll hear the case for balancing every single tool based on the long-standing ISO 1940-1 standard. |

However, machines were much slower 80 years ago. Back then, the most advanced machines would have spun larger, heavier tools at a maximum speed of about 4,000 RPM. If you applied the math from those days to today, you’d get unachievable values.

For example, the tolerances defined by G2.5 for tools with a mass of less than 1 pound rated for 40,000 RPM calculates to 0.2 gram millimeters (gm.mm.) of permissible unbalance and eccentricity of 0.6 micron. This isn’t within the repeatable range for any balance machine on the market.

Similarly, application-specific assemblies, for operations like back boring and small, lightweight, high-speed toolholders, can’t be accurately balanced for G2.5.

Machine tool builders rely on an outdated number, too, often basing spindle warranty coverage on using balanced tools at very specific close tolerances. While it’s true that poorly balanced tools run at high speeds wear a spindle faster, decently balanced tools performing common operations won’t wear spindles or tools drastically and deliver the results you’re looking for.

A Little Lesson About Forces

| In other words, if you’re rough milling with a heavy radial cut, the different forces will start bending the tool. When that happens, the cutting forces and all the feed forces will be substantially higher than whatever the unbalance forces might be. If that’s the case, it’s not that you take the unbalance force and add it to the cutting force and find your adjustment. |

Unbalanced tools are also blamed for issues that turn out to be misunderstandings about a machine’s spindle. I’ve visited shops with new high-speed spindles that had trouble running micro tools over 15,000 RPM. They rebalanced all the tools on the advice of their machine tool supplier, but to no avail. It turned out the machine was tuned for higher torque and higher cutting forces. Before going to the effort of balancing toolholders, work with your machine builder to understand where a spindle is tuned.

Not only is balancing tools rarely necessary, it can also be risky. Our inherently asymmetrical fine-boring heads are a good example. Because we balance them at the center, a neutral position of the work range, you lose that balance if you adjust out or in.

To adjust, you’d typically add weight to the light side, which can be a problem for chip evacuation and an obstructor. Or you can remove weight from the heavy side, but that means you have to put some big cuts on the same axis of the insert and insert holder, ultimately weakening the tool.

In longer tool assemblies, common corrections made for static unbalance can also cause issues. It happens when a toolholder is corrected for static unbalance in the wrong plane; i.e., adding or removing weight somewhere on the assembly that’s not 180 degrees across from the area where there’s a surplus or deficit.

Once the tool is spun at full speed, those weights pull in opposite directions and create a couple unbalance that often worsens the situation.

A Cautionary Tale

As a cautionary tale, consider a customer who was attempting to balance a batch of our coolant-fed holders. Based on the balancing machine, the operator drilled ¼-inch holes at the prescribed angle into the body of the holders. Not realizing what was inside, he drilled into cross holes connecting coolant flow and ruined several holders.

Tooling manufacturers are doing their part to avert disasters like this. For most, simple tools like collet chucks or hydraulic chucks are fairly easy to balance during manufacturing. We account for any asymmetrical features while machining and grinding holders and pilot each moving part, ensuring they’ll locate concentrically during assembly. These measures ensure the residual unbalance of the assemblies is very, very low and eliminate the need for balancing.

| Auto-balancing boring heads are designed specifically for the high-speed finishing I mentioned earlier, where unbalance force can be greater than cutting force. Our EWB boring heads, for instance, have a small internal counterweight that moves in direct proportion with each adjustment. Because the weight is carbide, it’s three times more dense than the steel in the tool carrier and is maintained inside the head’s symmetrical body. |

Save your balancing time and resources for high-speed fine finishing. If you do have work where balance is crucial, consider how the tools you buy are balanced and piloted out of the box and/or consult your partners before making any modifications.

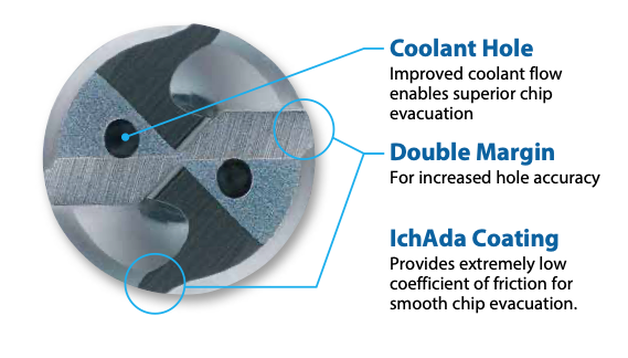

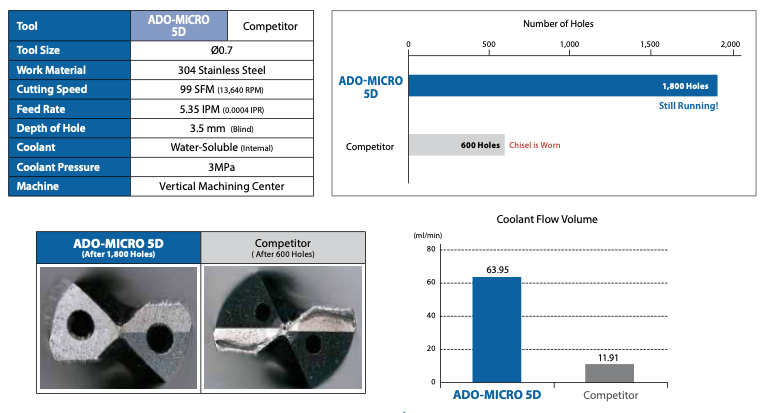

The ADO-MICRO features a unique double margin geometry with an extended flute and shortened end margin to enhance chip evacuation capability.

In addition to the outstanding chip ejection performance, the double margin configuration supports the straightness stability of the tool and reduces rifle marks on the inner surface of holes.

Furthermore, the ADO-MICRO features a pair of large oil holes and employs a hollow shank design to allow large coolant flow volume for trouble-free chip evacuation.

The ADO-MICRO is coated with OSG’s original IchAda coating that provides excellent surface smoothness in conjunction with high abrasion resistance and heat resistance to enable small diameter tools to achieve long tool life.

With the ADO-MICRO’s unique tool geometry and IchAda coating, non-step drilling is made possible even for deep-hole applications, enabling high processing efficiency.

Got an application you want to try this on? Give us a call!

Technical Support Blog

We set up this special blog for the most commonly asked questions and machinist data tables for your easy reference.

If you've got a question that's not answered here, then just send us a quick note via email or reach one of us on our CONTACTS page here on the website.

Authorship

Our technical section is written by several different people. Sometimes, it's from our team here at Next Generation Tooling & at other times it's by one of the innovative manufacturer's we represent in California and Nevada.

Archives

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

March 2019

January 2019

September 2018

June 2018

April 2018

February 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

August 2017

June 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

August 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

November 2015

August 2015

July 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

November 2014

August 2014

July 2014

December 2013

November 2013

September 2013

July 2013

March 2013

December 2012

March 2012

November 2011

May 2011

March 2011

January 2011

December 2010

November 2010

October 2010

Categories

All

5th Axis

Aerospace

Allied Machine

Aluminum Oxide

Angle Head

AT3

Balance

Bellmouthed Hole

Big Daishowa

Big EWA Automatic Boring

Big Kaiser

BIG Plus

Blue Photon

Bone Screws

Boring Tool

Carbide

Carmex Precision

CBN

Centerline Deviation

Ceramic Black

Ceramic End Mill

Ceramic Inserts

Ceramic Oxide

Ceramic Whiskered

Ceramic White

Chamfer

Champion Tool Storage

Chip Breaking

Circular Saw

Class Of Fit

CNC Lathe Tooling

Collet

Collet Chuck

Collet ER

Collet TG

Composites

Covid-19

Deep Hole Boring

Deep Hole Drilling

Drilling

Dual Contact

Dyna Contact Gage

Dyna Force Tool

Dyna Test Bar

EMO

End Mill

Exotap

Facemill

Fixturing

Fretting

Gaylee Saw

Hard Turning

Heimatec

Helical Interpolation

Hohl Shaft Kegel

How Its Made

HSK A

HSK-A

HSK E

HSK-E

HSK F

HSK-F

HXL Tap

Hy Pro Tap

Hy-Pro Tap

IMTS

Jergens

Kurt

Lang

Live Tooling

MA Ford

Maintenance Cart

Mapal

Martindale Saw

Material: Aluminum

Material: CFRP

Material: D2

Material: Hastelloy

Material: Inconel

Material: Peek

Material: Stone

Material Titanium

Material: VC 10

Material: VC-10

Metric Course Thread

Metric Fine Thread

Metric Thread Chart

Microconic

Micromachining

ModLoc

Modular

Mogul Bars

MPower

No Go Too Loose

NTK

NTK HX5

On Site Training

OptiMill-SPM

OSG Tap & Die

Oversized Thread

Parlec

PCD

PCT Firm Hold

Platinum Tooling

Projection Length

Pull Studs

Reamer

Retention Knob

Rotary Toolholders

Rotary Toolholders BT

Rotary Toolholders CAT

Rotary Toolholders HSK

Rotary Toolholders Hydraulic

Rotary Toolholders Shrink

Rough Thread

Runout

Runout Axial

Runout Radial

Safe-Flex

Saw Selection

Short Tap Life

Sialons

Silicon Nitride

Smart Damper

Speed Increaser

SpeedLoc

Speroni STP Essntia

Spindle Mouth Wear

Surface Roughness Ra

Surface Roughness RMS

Swiss

Swiss Machining

Taper Wear

Tapping Feed

Tapping; Form

Tapping IPM

Tapping: Roll

Tapping RPM

Tapping Speed

Tap Tolerance

Technical Training

Technicrafts

Techniks USA

Thread Milling

Thread Whirling

T.I.R.

Tolerance

Toolchanger Alignment

Toolholder Taper

Tool Presetter

Torn Thread

Troubleshooting

UNC Thread Size

Undersized Thread

UNF Thread Size

Unilock

Vises

Washdown Tool

Workholding

About

|

© 2024 Next Generation Tooling, LLC.

All Rights Reserved Created by Rapid Production Marketing

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed