|

For all BIG KAISER fine boring heads type AW, EW, EWN, EWD, EWE, EWB and EWB-UP, the frequency for lubrication depends on use.

If used daily, the recommendation is to oil the boring head every two to three months. The best procedure is to range the cartridge to the maximum diameter. Using a lubrication gun, pump oil in the unit until it stops accepting oil and then range cartridge to minimum setting. Excess oil will come out around the dial face (this is normal). If oil is excessively dirty, repeat the process. Recommended oils are Mobil Vactra No. 2, BP Energol HLP-D32, Kluber Isoflex PDP 94, or a similar light machine oil.

0 Comments

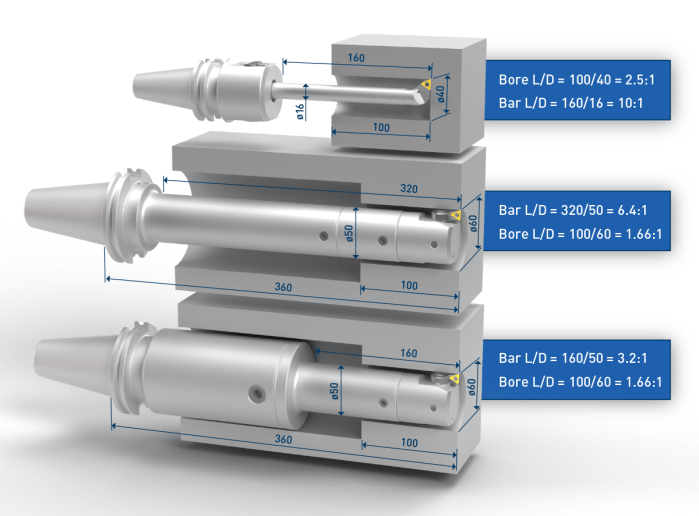

The L:D ratio of a tool assembly is calculated by using the length of the bar (or body) of a tool assembly and the diameter of the tool, not the workpiece bore diameter and depth.

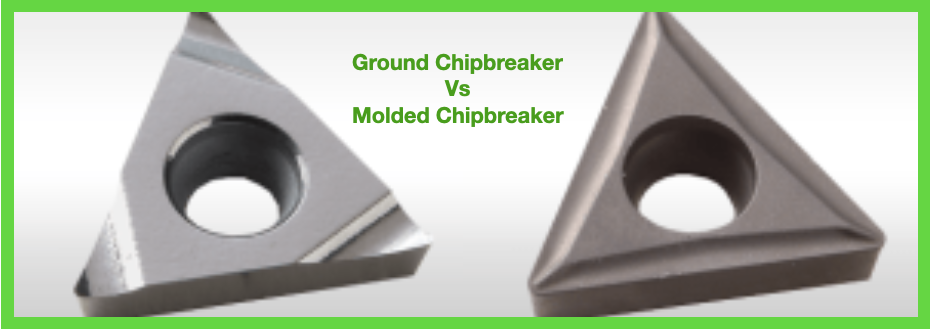

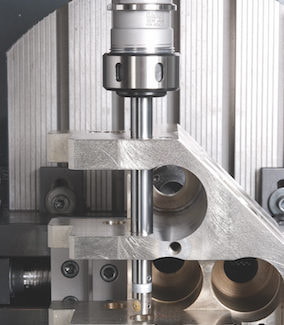

To expand on this concept, we see in the first configuration below the Ø16mm bar is sticking out 160mm which is a 10:1 although the bore is only a 2.5:1. In some applications this extra reach is needed to get around a fixture or a feature of the part. However, in those cases where it is not needed, decreasing the overhang by 55mm means the new L:D of 105:16 is 6.5:1. This alone would represent approximately 10x increase in cutting speed by increasing from 20mm/min vs. 200mm/min. The use of modular reductions has also been found to be a good strategy to improve tool performance. Comparing the lower two assemblies below, the middle assembly uses the same connection size for the length of the tool, ignoring the larger access diameter, and results in a 6.4:1 ratio. When a shank with a larger connection size is used along with a modular reduction, the ratio is halved, and provides a 350% productivity improvement (14mm/min to 50mm/min). In all cases, reducing the L:D ratio provides an improvement in speed which then provides longer tool life, better surface finish and size control of the bore. A common question asked for boring operations is when would I use a ground chip-breaker vs. a molded chip-breaker? A ground chip-breaker is recommended for chip control issues. The high-positive rake angle will help to make shorter chips, and the chip groove orientation forces the chips forward to more easily evacuate them from the bore, especially when used with high-pressure coolant through the tool. Ground chip-breaker inserts also provide lower cutting forces, so they are better suited for deep-boring or long-reach applications, and other situations where part or tool stability may not be optimal. Ground chip-breakers are also recommended for tight-tolerance applications where stock allowance is typically light for the final size pass. A molded chip breaker is recommended for stable applications in short-chipping materials. Because these situations don’t require a super-sharp edge for cutting the material, these inserts hold their edge longer for better tool life, and in most cases are less expensive. A Primer on Types of Chips

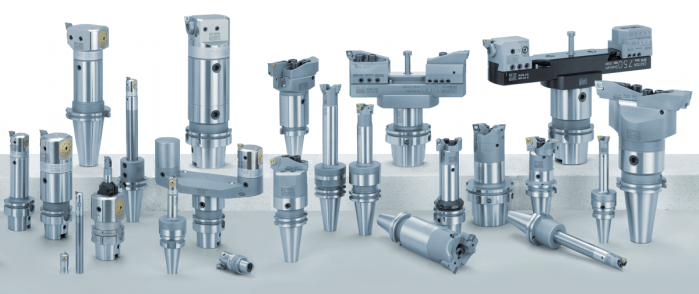

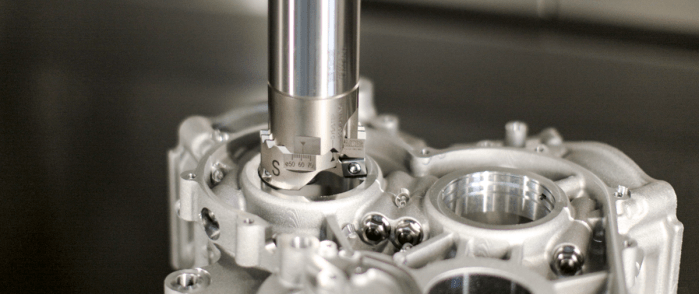

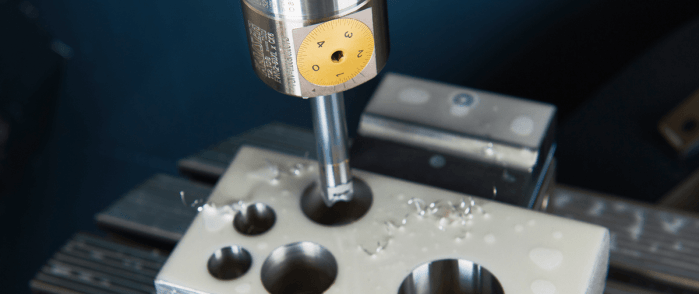

Put simply, the manufacturing process of boring is enlarging a hole in a piece of metal. There are quite a few different pieces of machinery or approaches that can be used to make holes from lathes and mills to line boring or interpolation. We wanted to do a quick break down of the different kinds of boring tools available to bore holes and/or secondary boring operations. Boring BarsBoring deep holes can involve extreme length-to-diameter ratios, or overhang, when it comes to tooling assemblies. Since it can be difficult to maintain accuracy and stability in these scenarios, we need boring bars to extend tooling assemblies and while maintaining the rigidity to make perfect circles with on-spec finishes. Solid boring bars Typically made of carbide for finishing or heavy metal for roughing, solid boring bars have dense structures that make for a more stable cut as axial force is applied. Damping bars When cutting speeds are compromised, or surface finishes show chatter in a long-reach boring operation, damping bars are an option. They have integrated damping systems. Our version, the Smart Damper, works as both a counter damper and friction damper so that chatter is essentially absorbed. Boring HeadsBoring heads are specifically designed to enlarge an existing hole. They hold cutters in position so they can rotate and gradually remove material until the hole is at the desired diameter. Rough boring heads Once a bore is started with a drill or by another method, rough boring heads are the choice for removing larger amounts of material. They are built more rigid, to handle the increased depths of cut, torque and axial forces needed to efficiently and consistently make the passes to remove materials. Fine boring heads Fine boring heads are best used for more delicate and precise removal of material that finishes the work the rough boring head started. They are often balanced for high-speed cutting since that’s the best approach for reaching exact specifications. Twin cutter boring heads Most boring heads feature one cutter that cuts as its feed diameter is adjusted by the machine. There are twin cutter boring heads that can speed up cutting and add versatility. For example, the Series 319 and other BIG KAISER twin cutter boring heads include two cutters that can perform balanced or stepped cutting without additional accessories or adjustments by switching the mounting locations of the insert holders that have varied heights. Digital boring heads Traditionally, adjusting boring heads has been painstaking and time-consuming, especially when it’s done in the machine. It’s easy to make mistakes when maneuvering to read the diameter dial and adjusting it to the right diameter. Digital boring heads have a LED that makes precise adjustments much easier. Starter DrillsSince cutters are on diameter of boring heads and not their face, they are not able to initiate a hole on a flat surface or raw material. Especially in smaller bores, fluted drills called starter drills can be used to get the hole started before rough boring.

Specialty boring heads Back boring and face grooving heads, as well as chamfering insert holders, are available for some of the most common secondary operations, after a hole is bored. We produce specific heads with cutters at the appropriate angles so each of these operations can be done without manually moving the part, changing the tool or adjusting the cutter angle. Modular boring tools Since limiting length-to-diameter ratios is so crucial to boring success, it’s extremely valuable to be able to make your tooling assembly as short as possible. Our modular components are based on a cylindrical connection with radial locking screw that allows for the ideal combination of different kinds of shanks, reductions and extensions, bars, ER collet adapters and coolant inducers. Looking for some help finding the right boring equipment for your next job or new machine? Our engineers are here to help. Get in touch with us here. The four critical requirements for tool holders are clamping force, concentricity, rigidity, and balance for high-spindle speeds. When these factors are dialed in just right, there’s nearly no chance of holder error and considerable cost reduction is achieved thanks to longer tool life and reduction of down-time due to tool changes. Easier said than done, our experts shared some of their best, quick-hitting advice for top tool holder performance in different situations. 1. Balance holders as a complete assembly Long-reach milling has some unique demands; when setting up this type of job, always balance tool holders as a complete assembly. While many tooling providers pre-balance their holders at the factory, it’s often inadequate, especially for long-reach applications. 2. Holder damage can go from bad to worse quickly Wear and tear on holders can be costly in the end, but there are ways to protect against it. Inspect and care for your holders. Trauma on a holder or spindle—dings, scratches, gouges, etc.—can magnify quickly. One bad holder can spread its problems like an illness. If you’re seeing disruptions like these on your holders, get them out of the rotation. 3. The rule of thumb on holder dimensions Looking for affordable ways to avoid vibration? Start by opting for a holder with a combination of the largest diameter and shortest length possible. 4. Rigidity can harm tapping operations What many don’t realize about tapping operations is that a perceived strength of collet chucks—their rigidity—can actually be detrimental. Rigidity does very little to counteract the dramatic thrust loads imposed on the tap and part, exacerbating the already difficult challenge of weathering the stop/reverse and maintaining synchronization. 5. Balancing is crucial to five-axis machining Five-axis machining introduces a whole new set of tooling challenges. While important in any type of machine, balance may be of most importance in full five-axis work. A well-balanced holder helps ensure the cutting edge of the end mill must be consistently engaged with the material in order to prevent chatter and poor surface finish quality. 6. Consider spindle speed requirements when choosing between shrink-fit and hydraulic holders If you have to choose between shrink-fit and hydraulic holders in a long-reach application, consider the spindle speed required. If a hydraulic chuck exceeds its rated RPM, fluid is pulled away from the holder’s internal gripping gland, causing loss of clamping force. But when used within its recommended operating range, a hydraulic tool holder offers superior runout and repeatability. On average, a good shrink-fit holder has about 0.0003-inch runout, while a hydraulic chuck offers 0.0001 inch or better. 7. Don’t overlook the tool’s effect on holder performance The cutting tool affects holding ability more than most machinists and engineers realize:

8. Not all dual-contact tooling is the same Anyone in the market for BIG-PLUS dual-contact tooling should consider this simple statement: Only a licensed supplier of BIG-PLUS has master gages that are traceable to the BIG grand master gages and have the dimensions and tolerances provided to make holders right. Everyone else is guessing and using a sample BIG-PLUS tool holder as their own master gage—a practice that any quality expert will advise against. Look for the marking: “BIG-PLUS Spindle System-License BIG DAISHOWA SEIKI.” 9. You may have a BIG-PLUS spindle and not even know it You’d be surprised how often we hear from our certified regrinders or engineers in the field about folks that didn’t realize their machine had a BIG-PLUS spindle—the message can get lost in the supply chain or during the sales process. The easiest way to know if an interface is BIG-PLUS is to place a standard tool into the spindle and see how much of a gap there is between the tool holder flange face and spindle face. Without BIG-PLUS, the standard gap should be visible, or about 0.12 in. If it is BIG-PLUS, the gap is half of this amount, or only 0.06 in. These values change depending on 30 taper, 40 taper or 50 taper sizes, but the gap is visibly less than usual. 10. Use positive offsets during holder setup It may be how it’s traditionally been done but touching off holder assemblies in each machine to establish negative tool offsets based on the zero-point surface—the vise, machine table, workpiece, etc.—is not the most efficient process. We think the choice is pretty clear: adapting machines to a single presetter so they can receive positive gage lengths is superior to using all types of machine-specific negative offsets.

This is a change to “the way things have always been done” that can be met with some resistance, but in the grand scheme of things, it’s a relatively small and simple step that makes life much easier. It’s a relatively low-cost opportunity to introduce more standardization of holder setup to the shop floor. Holders are the bridge between the machine and the part. That’s a lot of pressure—literally and figuratively. It’s important to select, care for and use holders carefully from the day they are purchased until they’re tossed into the recycling bin. From collet chucks to coolant inducers, BIG KAISER is North America’s source for standard-bearing tool holders that guarantees high performance. Explore the full lineup. It’s time for machine tool builders and machining companies to shelf the long-standing ISO 1940-1 standard in favor of ISO 16084:2017. Not only is balancing tools rarely necessary, it can also be risky. A lot of conflicting information has circulated over the years about balancing tools. As an author of the new standard for calculating permissible static and dynamic residual unbalances of rotating single tools and tool systems – ISO 16084:2017 – allow me to clear some things up and, hopefully, make life a little easier for you.

Since its institution in 1940, the G2.5 balance specification has been widely accepted across the industry; i.e., “it’s how things have always been done.” However, machines were much slower 80 years ago. Back then, the most advanced machines would have spun larger, heavier tools at a maximum speed of about 4,000 RPM. If you applied the math from those days to today, you’d get unachievable values. For example, the tolerances defined by G2.5 for tools with a mass of less than 1 pound rated for 40,000 RPM calculates to 0.2 gram millimeters (gm.mm.) of permissible unbalance and eccentricity of 0.6 micron. This isn’t within the repeatable range for any balance machine on the market. Similarly, application-specific assemblies, for operations like back boring and small, lightweight, high-speed toolholders, can’t be accurately balanced for G2.5. Machine tool builders rely on an outdated number, too, often basing spindle warranty coverage on using balanced tools at very specific close tolerances. While it’s true that poorly balanced tools run at high speeds wear a spindle faster, decently balanced tools performing common operations won’t wear spindles or tools drastically and deliver the results you’re looking for. While it’s true that poorly balanced tools run at high speeds wear a spindle faster, decently balanced tools performing common operations won’t wear spindles or tools drastically and deliver the results you’re looking for. A Little Lesson About ForcesThis all begs the question: When do you need to take the time to balance holders? I would argue that tools require balancing only if they’re notably asymmetrical or being used for high-speed fine finishing. Here’s a rule I’ve long followed: If cutting forces exceed centrifugal forces due to unbalance, high-precision balancing isn’t needed because the force required to balance the tool will most likely be less than cutting forces.

At that point, aggressive cutting – not unbalance – is going to damage the spindle. Unbalanced tools are also blamed for issues that turn out to be misunderstandings about a machine’s spindle. I’ve visited shops with new high-speed spindles that had trouble running micro tools over 15,000 RPM. They rebalanced all the tools on the advice of their machine tool supplier, but to no avail. It turned out the machine was tuned for higher torque and higher cutting forces. Before going to the effort of balancing toolholders, work with your machine builder to understand where a spindle is tuned. Not only is balancing tools rarely necessary, it can also be risky. Our inherently asymmetrical fine-boring heads are a good example. Because we balance them at the center, a neutral position of the work range, you lose that balance if you adjust out or in. To adjust, you’d typically add weight to the light side, which can be a problem for chip evacuation and an obstructor. Or you can remove weight from the heavy side, but that means you have to put some big cuts on the same axis of the insert and insert holder, ultimately weakening the tool. In longer tool assemblies, common corrections made for static unbalance can also cause issues. It happens when a toolholder is corrected for static unbalance in the wrong plane; i.e., adding or removing weight somewhere on the assembly that’s not 180 degrees across from the area where there’s a surplus or deficit. Once the tool is spun at full speed, those weights pull in opposite directions and create a couple unbalance that often worsens the situation. A Cautionary TaleIf you do go down the balancing road, you’d better know where you can modify tools, what’s inside, how deep you can go, and at what angles. Whether you’re adding or removing material on a holder, I highly recommend consulting the tool manufacturer for guidance first. As a cautionary tale, consider a customer who was attempting to balance a batch of our coolant-fed holders. Based on the balancing machine, the operator drilled ¼-inch holes at the prescribed angle into the body of the holders. Not realizing what was inside, he drilled into cross holes connecting coolant flow and ruined several holders. Tooling manufacturers are doing their part to avert disasters like this. For most, simple tools like collet chucks or hydraulic chucks are fairly easy to balance during manufacturing. We account for any asymmetrical features while machining and grinding holders and pilot each moving part, ensuring they’ll locate concentrically during assembly. These measures ensure the residual unbalance of the assemblies is very, very low and eliminate the need for balancing.

Decades of the same standards have conditioned us to think a certain way about balancing tools. While it seems logical that every tool must be balanced, it’s just not the case: Many issues attributed to unbalance aren’t caused by unbalance, and the risks of balancing every single tool often aren’t worth the reward.

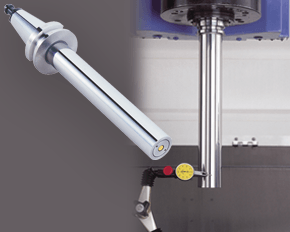

Save your balancing time and resources for high-speed fine finishing. If you do have work where balance is crucial, consider how the tools you buy are balanced and piloted out of the box and/or consult your partners before making any modifications. A machine’s spindle is one of the key links in the machining chain. In other words, if there are irregularities inside or at the face, they can show up on your part. It makes regular inspection and spindle maintenance critical to getting the most out of your equipment and maintain process efficiency. These three accessories, the Dyna Contact Taper Gage, the Dyna Test Bar and the Dyna Force Measurement Tool, can help you perform this maintenance easily without eating into valuable spindle time. Dyna Contact Taper Gage

Dyna Test Bar

With the help of a dial indicator, you can uncover any runout while safely spinning the spindle at a very low RPM and verify the parallelism of Z-axis motion. Dyna Force Measurement Tool

The Dyna Force measurement tool provides a precise digital reading that reveals reduction in retention force in increments of 0.1kN. If you would like a demonstration for any of these tools contact us or set up an appointment for one of our Next Generation Tooling engineers to visit you!

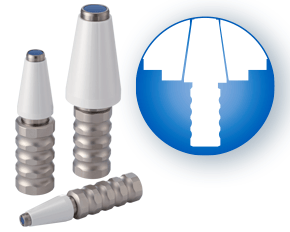

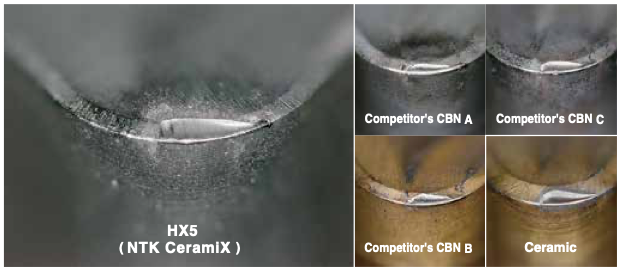

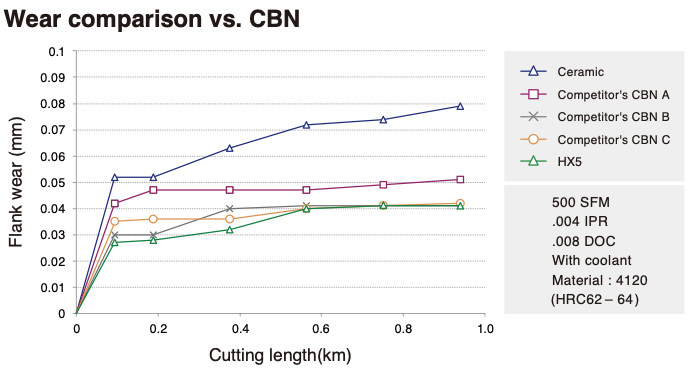

NTK CeramiX HX5 replaces CBN NTK developed this latest game changing ceramic material NTK CeramiX HX5 to replace CBN. As a ceramic cutting tool specialist, NTK has been researching new advancements for ceramics in the industry for decades. They recently introduced a new grade that matches CBN on performance. The new CeramiX "HX5" grade provides a cost saving solution for hard turning applications. It's designed for Hard Turning with continuous cut in the Hardness range of 55 to 66HRc

|

Technical Support BlogAt Next Generation Tool we often run into many of the same technical questions from different customers. This section should answer many of your most common questions.

We set up this special blog for the most commonly asked questions and machinist data tables for your easy reference. If you've got a question that's not answered here, then just send us a quick note via email or reach one of us on our CONTACTS page here on the website. AuthorshipOur technical section is written by several different people. Sometimes, it's from our team here at Next Generation Tooling & at other times it's by one of the innovative manufacturer's we represent in California and Nevada. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

About

|

© 2024 Next Generation Tooling, LLC.

All Rights Reserved Created by Rapid Production Marketing

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed